During the 2022 Catalysis Lean Healthcare Transformation Summit, Duke HomeCare & Hospice (DHCH) was one of two Value Capture clients that presented (the other being WellSpan Health and we’ll blog about their session soon).

If you don’t work in home health or hospice, please keep reading! There are great tips and tactics here that you could use in any setting. Are you struggling with staff turnover? If so, this post is for you!

This post captures highlights and key points from the DHCH learning session titled, “Using Rapid Cycle Learning System to Tackle Turnover.” The presenters were Cooper Linton, Associate Vice President, and Janet Burgess, Director, Home Health.

Summary of Key Results

What did they accomplish?

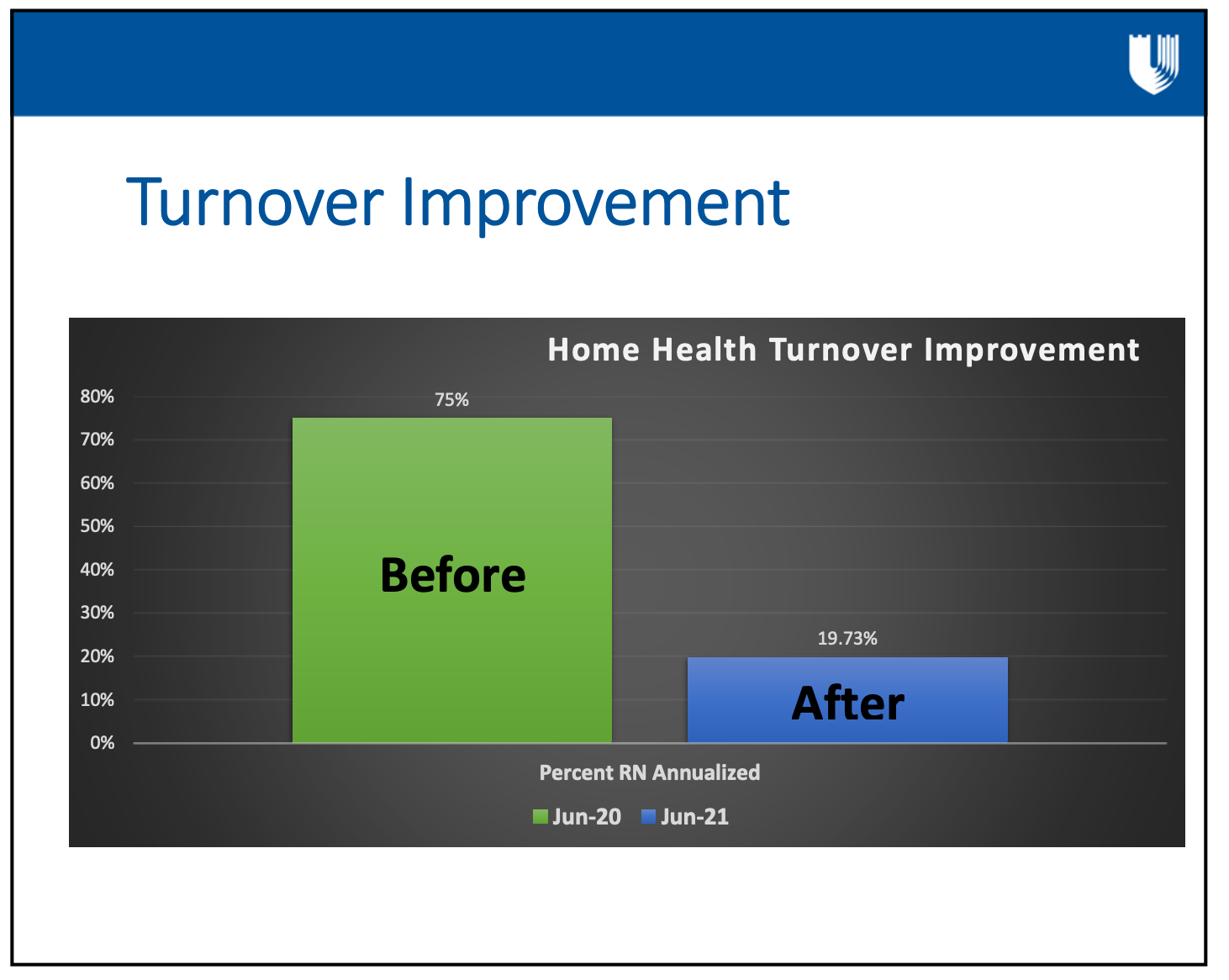

- Reduced nursing turnover from 75% to 19% in just one year, during Covid times (the national average turnover is about 64%)

- Saved $4.5 million in recruitment and retention costs

- Captured lost revenue of $17.5 million (patients previously turned away due to lack of staff)

Wow! How did they accomplish that?

Some key actions that drove success:

- Leader buy-in, within Home Health, DHCH and at the Duke Health System level

- Keep track of improvement activities, progress, and results

- Encourage and support engagement from staff at all levels

- Use information analyzed and collected from evaluations of improvement activities to quickly pivot and make changes

- Use rapid cycle learning as a catalyst for continual change toward improvement

- Keep all staff updated frequently on improvement activities and outcomes

What can you learn from them so that you can drive results like this in your organization?

Keep reading for more details...

Previously Shared by DHCH

By the way, you can gain more insights into how DHCH significantly reduced nursing turnover, improved several processes to reduce waste in improve employee engagement, and improved its leadership approach and management system:

Webinar:

“Applications of Lean Leadership Methods in Home-Based Care,”

Podcast Episode:

“Leadership for Safety, Problem Solving, and Continuous Improvement at Duke HomeCare and Hospice.”

White Paper:

"Continuous Learning Leads to Continuous Improvement"

Who is DHCH and What Do They Do?

Cooper Linton began the session by saying, “I will personally tell you I think we are changing the direction of home-based care now. I think COVID accelerated that. We need to begin to think about the way we deliver care at home, not just from an efficiency perspective or a technology perspective, but also from a health equity perspective.

We can have all the conversations we want about social determinants of health, but until you’ve sat in someone’s living room, looked in their refrigerator, seen their bedroom, looked in their bathroom, you don’t know them. And even that doesn’t give us a full picture. But we begin to get insight into people’s lives and the way healthcare is delivered, through the intimacy of being invited into someone’s home. It totally changes the way we engage with our patients.”

DHCH has three business lines, serving the entirety of three states, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia. These are:

- home health, which includes nursing and aide care

- therapies, such as occupational and physical

- speech therapy

- social work

- hospice care (in-home, in-hospital and a freestanding hospice facility)

- home infusion

- pharmacy compounding services

Cooper: “Our role is to do a couple of things. Obviously, to take care of sick people at home. But we’re also a pressure-relief valve for the Duke University Health System that has three hospitals.

When we begin to think about the role of community-based care, home-based care, I think there are really two buckets. One is decompression of acute beds [shifting care] to lower acuity and more cost-effective centers of care, which requires us to have a stable workforce to deliver that. The other [bucket] is to begin looking at pre-acute care, because the best way to avoid a re-admission is just don’t admit them. It’s also the best way to avoid a facility-acquired infection.

So we have to begin thinking about this differently, but it’s workforce-dependent. I keep going back to that same element.”

Employee Turnover is a Huge Opportunity (and Need)

It wasn't just an opportunity... they delivered improvement in a year, as you can see below:

Cooper: “This slide actually provides two things. One is ‘hey this is what we did and made it better.’ But the column on the left is not actually a bar graph. It’s a referendum by our staff on working for us. And they voted with their feet; 75% of the time, if they were a nurse, they left within one year.

That is crazy high, but the part that’s even more concerning is that, as an industry last year for home health, turnover cost home health 64%…. It’s an industry-killing statistic. We’re struggling with these numbers all the way across the health system. I think all of us are struggling with retention issues, recruitment issues, and frankly, engagement issues, where people don’t want to do this work anymore.

So we really needed to listen to the referendum, brutal as it was, and have a fearless and candid conversation with ourselves.

Let me touch on this very quickly. Lean principles are relatively new in home-based care. A lot of healthcare is not using them at all. There is very little penetration in home-based care, yet there is an incredible need for improved efficiencies [in addition to higher safety for patients and providers, quality, and other outcomes that we can achieve with Lean].

If the whole idea is to begin shifting care to the home environment, in many respects to gain efficiencies, but our modality of doing it is already inefficient, we’ve got a serious problem in both meeting the mission of care, and the very purpose of transferring that care into the community.

The idea has been that you can’t do Lean-based care here [in home health or hospice] because it’s totally different. Well, that’s an argument I think I’ve heard before - ‘you can’t do it here because we’re different, our patients are different, our doctors are different, our payers are different.’

Yeah, we are different, but it’s people and processes. That doesn’t sound different, we just need to figure out how we’re going to adapt to it. But we have not done that well in our industry.

So we have a highly dispersed workforce.... We have highly heterogenous and uncontrolled care settings, literally in the thousands. Just today alone, we’re treating 2,070 patients. That’s our normal average daily census of our three programs combined. We control the care setting for 12 of those patients. Twelve of them are in an in-patient hospice facility. The rest of them are in an environment that is not ADA-compliant, that does not have security, there’s nobody down the hall to help you, there’s no call button, there’s no environmental services.

There is a humility to engaging with patients where they live. That means that we have to adapt, today alone, to over 2,000 care settings. I love our staff, they’re amazing.

Security issues have become an increasing issue.... One of our staff members, very recently, knocked on the door. The patient knew we were coming, the son had significant untreated mental illness. Our staff was met and looking down a gun barrel. It’s a major concern for security.

When our staff members start to work here, day one, within the first 60 minutes, they will hear a safety conversation, typically from me.

We will have a conversation about their safety within the first 60 minutes of their employment, because this is critical to understanding how we deliver care and how we protect our workforce.”

Their Lean Journey – The Early Months

DHCH began its Lean journey about six months before the COVID pandemic hit the U.S. They started learning and implementing Lean methods in the in-patient hospice facility because it is the most like a hospital unit and it seemed the logical place to start.

Starting out, DHCH focused on tiered huddles, visual management, leader training, and leader standard work. It was then decided to build on the learnings from the in-patient facility to expand to the in-home workforce and convert all huddles to virtual so that everyone could participate.

Cooper: “This was, of course, essential in the pandemic, and required significant refinements of the tiered huddle processes. We need to have access to everyone’s voice. It gave us a structure to do rapid-cycle change.”

Avoiding 'the $22 Million Invoice': From 75% Turnover to 19% Turnover in One Year

Cooper: “The issue [with 75% nursing turnover] is we get hung up on the symptom. At least that’s what I think I did, I think that’s what a lot of other people did. We get hung up on the 75%, and then we said that’s really costing us a lot. It is, but I don’t think we have really learned to capture what I call the ‘silent P&L. [profit and loss]’ So I want to break this down a little bit.

This turnover for us as an entity cost us 2,500 patients a year that we could not accept. The hidden P&L on this is, if you figure very conservatively, $4.5 million for the turnover of recruitment and retention [costs]. You throw in lost revenue opportunity of $17.5 million, you’re talking conservatively $22 million.

I had just mentioned that we’re the pressure relief valve for three hospitals. That’s a lot of patients backed up in a lot of beds at a very high cost per day, and that’s not even counting the human cost of the patients that are laying in the E.D. or that are sitting in the E.D. waiting to be admitted, because you’re on red status and there’s no room.

At the end of our first year, had someone sent us a bill and said, ‘Here’s your turnover invoice, you owe us $22 million,’ we would’ve gone into a panic, we wouldn’t have known what to do, but that’s not what happens.

We start to get used to the turnover and we start to try to explain it away. ‘Oh, you know it’s regrettable turnover.’ Well then, it was probably very regrettable hiring. We have to own this, but we start trying to find ways to not deal with it, because then it’s our fault, right?

We looked at this and we realized that this is about to kill us. Then we realized it actually wasn’t as bad as it was – it got a lot worse.”

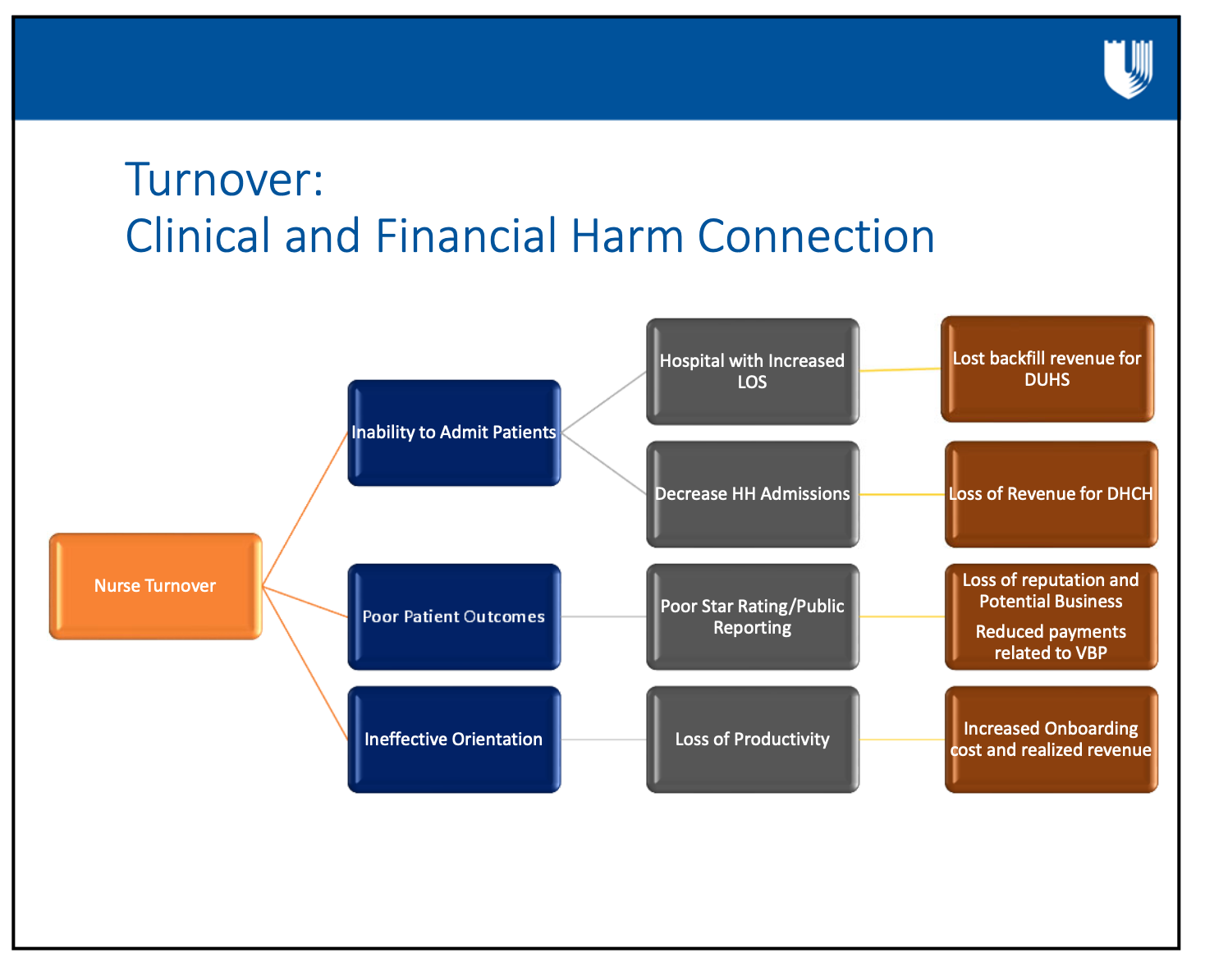

Cooper went on to explain that Duke is moving towards more ‘attributed lives’ on risk-based payor relationships. The high turnover among nurses negatively impacts acute LOS and lost Duke backfill revenue, additional E.D. volume for Duke University Health System, staff overburden and burnout, inefficiencies and quality metrics, and care outcomes negatively impacting value-based purchasing payments.

Homing in on Home Health

Home Health has an average daily census of about 700 patients, with about 70 clinicians (nurses, therapists and aides) delivering care in homes spread out in a seven-county area. Each nurse manages a caseload of about 30 to 40 patients at any given time.

Janet Burgess noted that, “Unlike providing care in a hospital, where there is a team of other clinicians down the hall to help when needed, home health providers don’t have that immediate support and help. These nurses have to be trained and be able to handle all these things independently in the home.”

In the 30 years that Janet has been in home health, patients are the highest acuity patient she’s ever seen, with complex conditions and care needs. “Our nurses are in the homes trying to care for these patients and trying to teach these patients how to care for themselves and improve their health, and in the meantime trying to keep them from going back to the hospital.

I’m telling you this because once we’ve trained a nurse and then they leave, it’s a huge impact because you just can’t put somebody in their place. You can bring in an agency nurse but you just can’t replace that [nurse]. So it’s critical that we did something about our turnover.”

See the next two slides that focus on the connections between clinical and financial outcomes from turnover, such as:

- increased LOS,

- poor patient outcomes and

- inability to backfill DUHS patients.

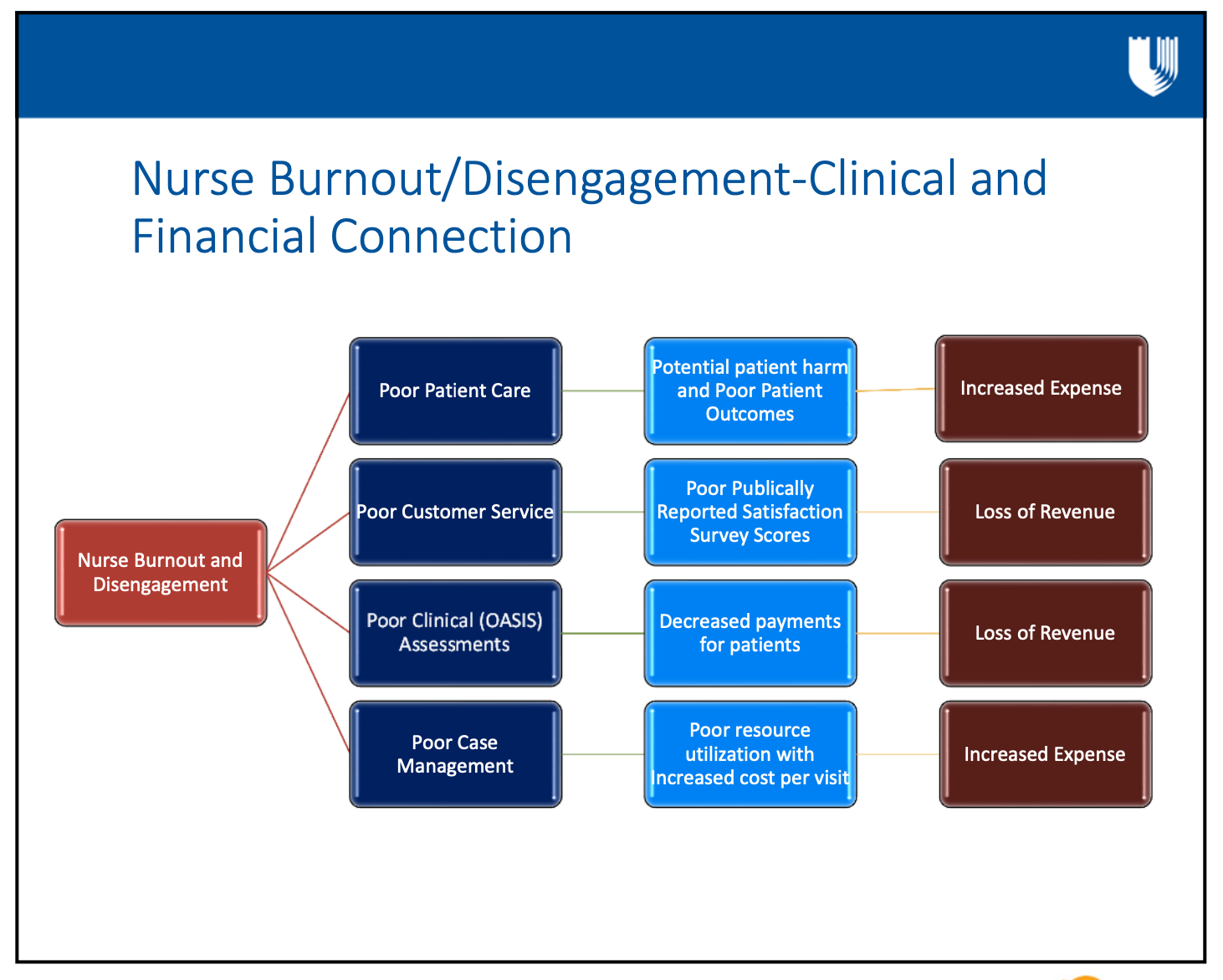

The second slide illustrates outcomes clinician impacts when nurses stay rather than leave, including:

The second slide illustrates outcomes clinician impacts when nurses stay rather than leave, including:

- burnout and lack of engagement,

- poor patient care and outcomes,

- poor case management,

- poor public satisfaction scores,

- greater risk of harm,

- loss of revenue.

Janet: “When we first started our journey in rapid-cycle learning, we started to try to determine the current condition and what was the root cause for all of our turnover. We pulled a group together, we pulled from the frontline, the people that were doing the work – it was really important that they were involved when we explored the current state – and we pulled in our leaders.

What they were telling us is that they were burned out, and that there were ineffective workflows. With the required documentation there’s a process that they were having to go through, and they said it was extremely frustrating for them. They were disengaged, they were seeing their team members leaving, it just was not a very happy time for anybody.

They were saying that the orientation and training we were providing, and the orientation was 10 weeks, wasn’t enough and that they weren’t getting what they needed to be successful to take care of these high acuity patients that we have.

They also reported that leaders were not listening to them, leaders weren’t hearing their feedback, and they didn’t feel like we were supporting them. It was pretty eye-opening. Ineffective workflows, especially around the documentation process, caused much back-and-forth, re-work, and led to clinicians working at night. They felt like leaders just didn’t care about them.

Changing from Transactional Leadership to Servant Leadership

Some key ways to shift toward servant leadership include:

- Build open and trusting relationships

- Build culture of inclusiveness and consensus

- Empower and motivate

- Focus on patient, staff, and caregiver safety and wellbeing

“So, we recognized that we had to change the way that we were leading. You know, it’s easy to make excuses or try to explain it away, but we needed to change the way we were leading. We, as a leadership team and as a Home Health leadership team, we had to take some risks and really change what we were doing.”

Janet: “The first thing was moving from a transactional leader to a servant leader. We had to build open and trusting relationships with our team members. And, how do you build trust? Well, it’s listening to them, being sincere and letting them know that we really wanted to hear what they were experiencing. Also, if you say you’re going to do something, you’ve just got to do it; if you don’t, then you completely lost their trust.

We had to be able to empower and motivate them and get them involved. It’s very easy, when you have a remote team and they’re out working in the community and they become disengaged or they become disconnected from the other team members. We had to find a way to pull them together. One of the ways we did this was by focusing on patient, staff and caregiver safety and well-being through our “Commit to Zero” initiative.”

Cooper then added, “When we first approached this problem, we were immediately told what the problem was. ‘The problem is your electronic medical record, so if you fix your electronic medical record, everything will be okay tomorrow morning.’

I don’t know of an EMR out there that’s going to correct for lousy workflows and overburden. In fact, I will make the argument that our workflows were so inaccurate, so poorly designed, that the worst possible thing we could have done is take overburdened staff and said ‘now you need to implement a new EMR.’ I’m very confident that we could have exceeded our 75% turnover.

Janet then continued:

“As leaders we also had to shift from being the ‘doer’ to being the ‘coach.’ That’s hard for me. I really made a lot of changes. You know because I was the type - as a leader, you fix it, right, it’s your responsibility to fix things and come up with the solutions. But really it’s not me doing that, it’s empowering our team members to learn and do and solve the problems.”

DHCH created work groups, involving a lot of different team members and involved them in everything the leaders were learning and doing. As more problem-solving responsibility was shifted to the frontline, leaders changed their work to support problem solving, rather than doing the problem solving.

Cooper elaborated on the challenges of overcoming a somewhat ingrained mindset of blaming others for problems. “We struggled with that at Duke. We had to culturally pull that back and have people who had never done this kind of rapid-cycle improvement get in a room and wrestle through this. I’ll be honest, I think the emotional navigation on this was a whole lot harder than mapping out the work.

Honestly, I think that breaking down the emotional navigation of the staff and dealing with it was part of that trust building. It was not easy, but it had to be an inclusive process, and it couldn’t just be our frontline staff because their jobs are not just impacted by our frontline nursing. It was a very large group, probably bigger than we would typically have liked for rapid cycle.”

Janet picked up on that thread. “That’s right, we had people from the Referral department all the way from our QA department, our schedulers, leaders, orientation, clinical practice, all of them were involved in this process.

Living a Culture of Real-Time Problem Solving

DHCH began to live the culture of RTPS, empowering and encouraging frontline workers to problem solve, with leaders becoming coaches of the frontline problem solving. Leaders also became active supporters and advocates for frontline problem solving.

Part of this culture, and to elicit continuing input from the frontline, leaders not only continued asking questions, but also went out in the field with frontline staff, into patients’ homes to experience the situations of the frontline.

A key element of management system of this RTPS culture was the tiered huddles. Using Zoom, every person in the office and on the road joined the tier one huddle to discuss safety issues and needs. As needed, issues would be raised up through subsequent tiers of huddles (including up to the Duke Health system level) so that proper support and help would be provided. Another benefit of the tier one huddles was the connections that were created and strengthened, and the huddles gave the teams the opportunity to celebrate solutions, great work and truly feel a part of the team.

With the use of rapid cycle learning, including two-week sprints to keep momentum going, DHCH achieved: redesigned workflows toward the ideal state, from referral through care and billing; reduced wasteful activities in the EMR; made improvements to the orientation process, such as increasing the length of time for orientation to ensure a strong foundation for new employees; modified workload and productivity elements, such as reducing the case management workload; and, made communications improvements.

Investing in New Nurses by Doubling the Orientation Period

A great example of how the leaders truly listened to the work groups is lengthening orientation time. DHCH doubled orientation from 10 weeks to 20 weeks for the nurses. Janet noted,

“That’s a major investment in our nurses, but the work group and the people involved felt like it is what was needed and we had to listen to them, to support that because that was what was needed to take care of these high acuity patients.”

Cooper then added that “The argument that we get is that’s incredibly expensive to orient people for the better part of six months. Compared to $22 million a year, though, it looks like a great investment.

We’re now a place that people want to come to work, so our cost of recruitment is beginning to go down. We also found that our A/R was cut by about 60-70%. Why? Well we quit doing things that screwed up the A/R. So again, if you fix the process, there’s all these positive consequences. We had all these hidden expenses that began to go away, and suddenly you realize you’re able to afford the investment in the staff.

"For those who say ‘we can’t afford [that investment in staff],’ we say, ‘really? But we can afford 75% turnover?’ We have to really think about it differently.”

Keys to Rapid Cycle Learning Success and Impacts

What do Janet and other Home Health leaders and staff see as the keys to success?

- Leader buy-in, within Home Health, DHCH and at the Duke Health System level

- Keep track of improvement activities, progress and results

- Encourage and support engagement from staff at all levels

- Use information analyzed and collected from evaluations of improvement activities to quickly pivot and make changes

- Use rapid cycle learning as a catalyst for continual change toward improvement

- Keep all staff updated frequently on improvement activities and outcomes

The impacts of the rapid cycle learning and improvement were significant. At least as important as the impacts is the fact that the learning and improvements continue; after all, as Janet emphasized, the ideal state is one which must be continuously sought. Home Health has so far achieved:

- Improved workflows

- Elimination of wasteful activities

- Decrease frustration

- Improved work culture and environment

- Highly trained clinicians

- Decreased turnover

Celebrate Achievements, Always Seek to Do Better, Face our Fears

Janet reiterated that in June 2020, nurse turnover was at 75%. One year later, turnover was just under 20%, and that rate is being maintained (even in this phase of “great resignation”).

“We’re still working. We can’t just say ‘oh, we’ve done it,’ we have to keep on with what we’re doing and doing the continuous improvement and looking for opportunities to grow and transform and become better.”

Cooper: “If I was limited to one metric to gauge the effectiveness of home-based care, particularly in home health, I’d use facility-specific 30-day readmissions. If someone comes out and goes home, are you able to keep them out? We look at everything in a 30-day world, but in reality, we have the data for 60 days, why aren’t we looking at that as well?

“I mean, the whole idea is not just to keep them home until the 31st day. We should be looking at this at 30 days and 60 days to see if we are making longitudinal change in patients where they live. Because if our goal is to keep them in the lowest cost environment, with the lowest risk of infections, it’s keeping them where they call home.”

Cooper continued, saying, “One of the things that’s going on is that we’ve not only achieved that as the best in the region, but our cost per patient on admission is also the lowest of any home health provider in the area. So we’re achieving a higher outcome at a lower spend, and we’ve cut our turnover by 70%.

That degree of change is also empowering us to be more efficient, spend less money collecting money, spend less money trying to find staff, and we’re now the place that people are starting to knock on our doors saying, ‘do you have a job?’ That allows us to begin to build a workforce for a lower cost of acquisition.

“We are people, everything that’s an asset for us has feet. And the referendum has changed now to where they’re sticking and staying. But we’ve had to change the way we engage with them.”

Now I want to talk about fear. I think that one of the things that holds us back is the fears that we have as leaders. Fears that we don’t want to get turned down, we don’t want to get shut off. Fear that we’re not going to get a requested thing approved, or fear that our staff couldn’t speak up to say ‘hey my job sucks.’

We needed to hear that, it is clear that when you ask your staff for their opinion and they give it to you, it can hurt. But it took a while to get them to where they had an unfettered opinion, because if they’re driven by fear, they won’t tell you why they hate their job, or why they hate the way you lead, or why they don’t trust their leadership. Whatever it is, they need to be liberated from that.”

Cooper then asked the audience to reflect on what they fear most, and to think about what that fear causes them to quit doing, or to not even contemplate doing.

“Sometimes our fears are so deep-seated that we don’t even confront what we could have done. We’ve just kind of written off our capacity to make change. So how do we change that? If we could conquer that, how would it change our role as a leader? What would it do to increase your capacity to engage, to build trust? What are we going to do differently?”

Intentional Impatience

This whole point is about rapid cycle change so between now and the time you catch a plane, what are we going to do differently? Because I think we’ve got to bring that urgency to the work. We get used to the pace of complacency, and we’ve got to bring this urgency, I love the term ‘intentional impatience.’ We’ve got to bring that sense of urgency to confronting the way we lead, confronting ourselves because I think most of the time what’s holding us back is us. We’re the problem. That’s a difficult thing to confront.”

Don't Miss Future Updates!

To make sure you are notified about the future webinar that will focus specifically on reducing staff turnover and their lessons learned, so be sure to sign up to receive:

Written by Melissa Moore

Ms. Moore’s responsibilities center on marketing and communications. Prior to joining Value Capture, she served as a Marketing Manager at Reed Smith, a global law firm. Other career steps include: co-founding and operating a trend-setting coffeehouse; securities lawyer; and, service and equipment sales.

Submit a comment