In retrospect, I heard it. A low rumble in the distance as I shoveled snow on the morning of the last Friday of January just before 7 a.m. I wondered about it briefly, almost subconsciously, and kept shoveling.

Then the sirens started.

The bridge nearest our house, one we drive over almost every day and that I frequently run over, had collapsed into the 150-foot deep hollow of one of Pittsburgh’s glorious urban parks.

If not for a two-hour school snow delay, hundreds more could have been on the bridge, including my daughter’s friends coming to pick her up on the way to the high school.

The next morning, I walked over and stood looking down at the wreckage. I could see the cars and the bus that had contained 10 members of the community who miraculously were just injured, and thankfully, not killed. By then, the expected details began to emerge of how long the bridge condition had been rated “poor” by the authorities (since 2011, with little follow-up to make it safe).

As I watched the NTSB team beginning their investigation, I found myself thinking about safety, leadership, and time.

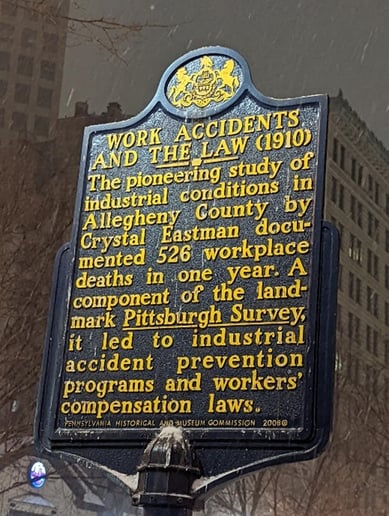

A Historical Plaque about Safety

Just a week before the bridge collapse, I’d been walking in Pittsburgh’s oldest section, Market Square. There, I found the plaque pictured here, memorializing the 1910 Pittsburgh Survey that included a first measurement of workplace deaths in a single year, finding 526 in Pittsburgh alone. The study and associated advocacy shocked the conscience of the power structures enough that government and unions stiffened their resolve to begin protecting workers, and efforts to stop trading human lives for production began, haltingly at first.

Eventually, leaders of industrial organizations themselves – management – emerged, who saw safety not only as a government mandate or union agreement to be grudgingly complied with, but as a moral imperative and a pathway to excellence. Value Capture’s founding non-executive Chair, Paul O’Neill, took up this mantle in the most profound way upon becoming Chairman and CEO of Alcoa in 1987. He used a quest for perfect safety as the linchpin of giving Alcoa the chance to be “habitually excellent,” ultimately becoming one of the world’s safest organizations (despite great danger involved in the work) and one of its most successful, financially.

Lessons from the Late Paul O'Neill

As I stood at the bridge collapse site, remembering the plaque, three linked concepts that Paul preached passionately came to me.

First, the principle that says, we don’t trade safety off against any other good, including money, or any other competing priority. Safety is like breathing, we do it as a precondition of any other activity.

The second is time. And here Paul usually emphasized “real time” as in, when we discover a risk or harm:

- We figure out the root cause in as close to real time as possible (24 hours was the standard at Alcoa)

- We fix the underlying problem in the system now (we do not punish people), and

- We share the identified risk and investigation openly and transparently, so all can see if they have the same risk themselves and not have to learn the same lesson first-hand

This is how you worked safety so that you were always moving forward, building capability to solve problems in a way that created or strengthened pride in excellence, never slipping back to more risk and more certain harm.

But in a complementary way, Paul also talked about time at the other extreme. A former Treasury Secretary and top leader of the White House Budget Office, he once said to me that American policymakers need to think about policy windows more like their Chinese counterparts, who think in centuries when they plan. And this centuries-long horizon led Paul to frequently talk about the importance of leaders focusing on legacy, about what would be left generations after they had left whatever organization they were leading – and, therefore, how to focus on the deepest, most important systems and culture building, for generational sustainability.

Safety as a precondition, and safety in both real-time and with a centuries-long view, combined powerfully in Paul O’Neill’s leadership through a belief in unleashing innovation – a belief in what people were capable of achieving if they were working together toward the right goal (zero harm), achieving things people thought weren’t possible, through creativity and problem solving.

What if the Bridge Had Been Managed This Way?

The collapsed Pittsburgh bridge was not managed with this framework. It was 50 years old, half a century. In a city with a declining tax base, inspections began turning up problems decades ago, as we see in a high percentage of other areas and American bridges, yet any attempted fixes were not sufficient to prevent the bridge’s condition from steadily worsening, not being restored to safety as a precondition.

“We don’t have the money” was the surrendering excuse.

And since every system produces exactly the results it is designed and operated to produce, this bridge ultimately failed, as a percentage of others have and others will if they are not managed in a way more in keeping with Paul O’Neill’s proven principles-based approach.

Imagine if, instead, Pittsburgh had turned its considerable power of innovation on the emerging problems, in real time and with a view to the centuries, leveraging transparency to mobilize the public and developing new, more efficient fixes and funding models, and even transportation and living patterns, to show how we can live safely while improving life, rather than settling for unsafe conditions. It might have been a quite different story. It still might be.

Lessons for Healthcare

If you are reading this story, you may, like us, lead in healthcare. Can we see the lessons and take action?

Most healthcare organizations effectively tolerated a high level of harm and risk to patients and employees, even prior to COVID. COVID hit the organizations with that mindset hardest, leading to greater rates of harm, stress, attrition, and financial instability.

Those organizations that had led with safety toward habitual excellence before COVID hit, in both real time and with a centuries-long view, have come through the first two years of the pandemic measurably better and stand ready to accelerate.

Others used COVID and the need to dramatically increase support for the front line, starting with safety, to get on this powerful journey.

Risk and harm are always all around us. The question is whether we are getting better or getting worse. It’s never too late to truly lead with safety.

Learn more about leading with safety in healthcare in "What Can Leaders Learn? What Can Leaders Do?"; "Hospital Command Centers: Keep What's Best and Improve the Rest"; and "Work is Really Difficult for Nurses Right Now. We Can't Just Return to the Old Normal." Learn more about Paul O'Neill, his leadership philosophy and approach, and his unwavering belief in zero harm for all, in two free eBooks, "A Playbook for Habitual Excellence: A Leader's Roadmap from the Life and Work of Paul H. O'Neill, Sr." and "Lasting Impact: Leaders Share Lessons from Paul H. O'Neill, Sr."

Submit a comment