Stop me if you have heard this before in your patient flow improvement work: “We just need to do ______, it’s best practice.” Your hospital may have even implemented some of these tools and practices, from mandating discharge huddles on every unit, to integrating clinical pathways or building discharge dashboards within the EMR, to creating admissions units and discharge lounges. There is nothing inherently wrong with any of these approaches, and they can be pieces of a successful patient flow toolkit. However, these “solutions” may not be addressing the actual root causes of the throughput problems your organization is experiencing. For example, clinical pathways are unlikely to have much impact when there are scores of patients with discharge barriers like lack of transportation. And implementing discharge huddles may help care teams to proactively identify and resolve those discharge barriers for individual patients but will do little to drive systemic improvement across the organization.

In this blog, we will discuss the importance of staying focused on lean principles and using a disciplined problem-solving process rooted in the scientific method BEFORE moving into tools and solutions.

Pitfall: Taking a tools approach; implementing solutions based on best practice recipes without understanding the problems your organization is experiencing.

The daily work of hospital leaders and staff involves managing patient flow, containing problems by identifying short-term countermeasures to improve flow, and working on large-scale projects to address the big, complex throughput problems. With so much research and literature on the subject, it can be tempting to just pull the next solution off the shelf or implement what worked at your last organization, but will it address the right problem? Have we done our analysis to know the key drivers in this environment? It is imperative we slow down and follow a scientific approach to problem-solving. Slowing down can feel counterintuitive with all the urgency to fix these issues, but if we are trying to solve to root and eliminate problems from recurrence, then we need to ensure we are doing our due diligence to understand the problem before identifying a solution. If not, we risk being back here again next year working on the same problem.

Do Instead: Apply Lean principles and scientific problem-solving to diagnose and design effective countermeasures.

Principles are universal truths that govern consequences and act on everyone, whether you know about them or not. Understanding and applying principles helps us to design systems that drive ideal behaviors, unlocking the benefits of the positive consequences. In the first post in this series, we touched on the criticality of the principle respect every individual and the importance of involving frontline caregivers. Engaging everyone in improvement drives numerous positive consequences, including improved morale and retention.

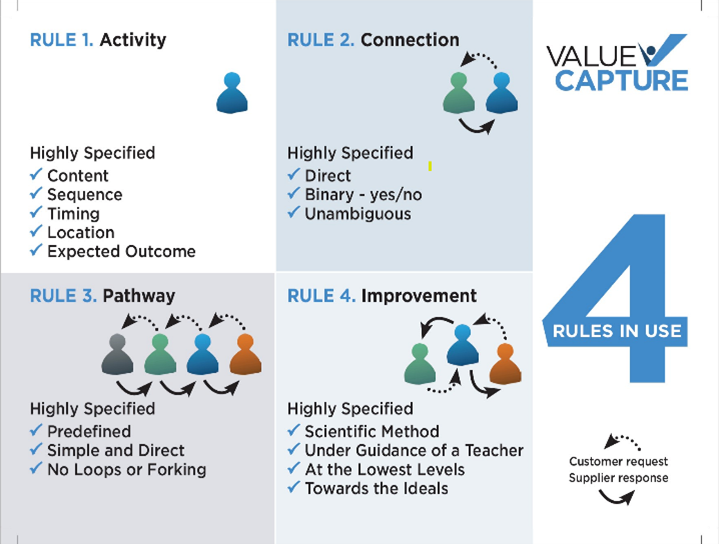

Other principles of critical importance in operational excellence are the Rules in Use, also known as the principles for designing, operating, and improving work. The Rules in Use are the result of a four-year research study conducted by Steven Spear and H. Kent Bowen in the 1990s to understand the Toyota Production System. See the Harvard Business Review article “Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System” published in 1999 for a deeper dive.

- Rule 1 – Activity Rule (How People Work): All work shall be highly specified as to content, sequence, timing, location, and outcome.

- Rule 2 – Connection Rule (How People Connect): Every customer-supplier connection must be direct, and there must be an unambiguous yes-or-no way to send requests and receive responses.

- Rule 3 – Pathway Rule (How the Process Is Constructed): The pathway for every product and service must be simple and direct, with no loops or forks.

- Rule 4 – Improvement Rule (How We Continuously Improve the Process): Any improvement must be made in accordance with the scientific method, under the guidance of a teacher, at the lowest possible level in the organization, toward the ideal. Ideal = physically and psychologically safe for all involved; defect free; meeting each customer or patient’s needs one-by-one, immediately, on demand; without waste

There is a ton to unpack in these principles, which could easily fill multiple blog posts and still not do them justice. To keep it simple for the purpose of this discussion, the key is that viewing patient flow through the lens of these principles allows for diagnosing and solving throughput problems more effectively. Whenever we see one or more of the rules being violated in our processes, we can be confident we have dug deep enough to get to root causes, and knowing which rules were violated gives us clues to potential countermeasures. See the example below to illustrate this concept:

Problem: We frequently have delayed discharges because consultant physicians have not yet signed off on the patient’s care.

Root causes:

- We have multiple ways of contacting consultants, such as phone calls, text messages, or catching them in the hallway (pathway rule violation; forks in the process).

- Sometimes we do not contact the consultants or do not get a response from them (connection rule violation; communication is not direct and unambiguous).

- Sometimes we contact consultants before the primary physician has written the discharge order and sometimes, we contact them after (activity rule violation; timing of consultant signoff is not specified).

- Efforts to address this problem have not involved the frontline care team members (improvement rule violation; not problem-solving at the lowest possible level).

Hypothesis/Countermeasure: If we specify one method for contacting consultants to signoff, make contact a specified number of hours before anticipated discharge, and have all consultants signed off before the discharge order is written, then we will have fewer discharge delays, thereby decreasing our hospital length of stay for admitted patients.

Experiment Using PDCA: Design an experiment with the hypothesis above in mind and input of your frontline caregivers that can rapidly be put in place for learning, adjusting, and designing the next experiment.

Applying the Rules in Use in this manner provides a simple but powerful framework for getting to ideas you can rapidly design, test, iterate on, and spread to others. We can also apply this same thinking from a broader vantage point to see complicated pathways, broken customer-supplier connections, vaguely defined activities, and unscientific improvement efforts across the system. The positive consequences of leveraging these principles include more effective problem-solving and improved patient flow.

Check out our other blog on common pitfalls when addressing patient flow

Learn more about how to improve patient flow with no tradeoffs

This blog was a collaboration between Senior Advisors, Alison Hartman and Anthony Pepe.

Written by Value Capture, LLC

We are consultants who act as trusted advisors that guide health systems determined to produce perfect health with zero harm, wait, or waste — for patients, teams, and communities. We work with organizations by solving their biggest problem and doing it in a sustainable way, with “no tradeoffs” leading to exceptional change in organizations and the knowledge to continue to improve.

Submit a comment