Recently, Ken Segel and Mark Graban (both from Value Capture) presented a webinar titled:

Seizing the Healthcare Safety Opportunity: Using the “Playbook” of Paul O’Neill

You can watch the entire recording, or you can listen to the audio of it via our "Habitual Excellence" podcast series (Episode 72). The full transcript, with a few of the slides for visual support, also appears below:

Transcript:

Mark Graban (2s):

Well, hi everybody. Thank you for joining us for today's webinar. It is titled, "Seizing the Healthcare Safety Opportunity Using The Playbook of Paul O'Neill."

Mark Graban (1m 28s):

I'm Mark Graban, a senior advisor with Value Capture, and I'm also the director of strategic marketing for our firm. And I'm joined today by Ken Segel, our CEO and one of our co-founders.

Ken, let me turn it to you.

Ken Segel (2m 4s):

Yeah, so I just wanna say it's great to be with everyone and, and past colleagues, current colleagues, future colleagues, those we've learned with. So thank you for joining us to talk about Paul O'Neill's powerful framework, rooted in the imperative of workforce safety and patient safety. And, you know, it's one that we both think is timeless, but also particularly powerful for this current moment of great challenge that we face in healthcare. You know, and Paul was someone who started as a young bottom of the wrong engineer in the, in rural Alaska, and worked his way up to become the head of the domestic section of the Office of Management and Budget, and then the president of the International Paper, and then the CEO of Alcoa, and then the US Treasury Secretary.

Ken Segel (2m 57s):

And along the way there, toward the end, he was acting as mentor to Mark and I and many other people on this call, and many others in his first role, in his role as our first non-executive chairman at Value Capture. So we're privileged to have learned with him, seen what he enabled in human achievement and to be with you here today.

Mark Graban (3m 16s):

And then real quickly, some of you may be very new to value Capture if you've heard about the webinar on social media. Just real quickly, Value Capture is a trusted advisory firm that supports the chief executives who seek to transform the performance of their healthcare organizations in safety, quality, and profitability. We invite you to learn more again at our website, valuecapturellc.com. So just to set some context here of why we're talking about this today, why we're sharing thoughts and practices and playbook from polls. Let's start off with a quick dig. You know that a hospital is one of the most hazardous places to work.

Mark Graban (3m 57s):

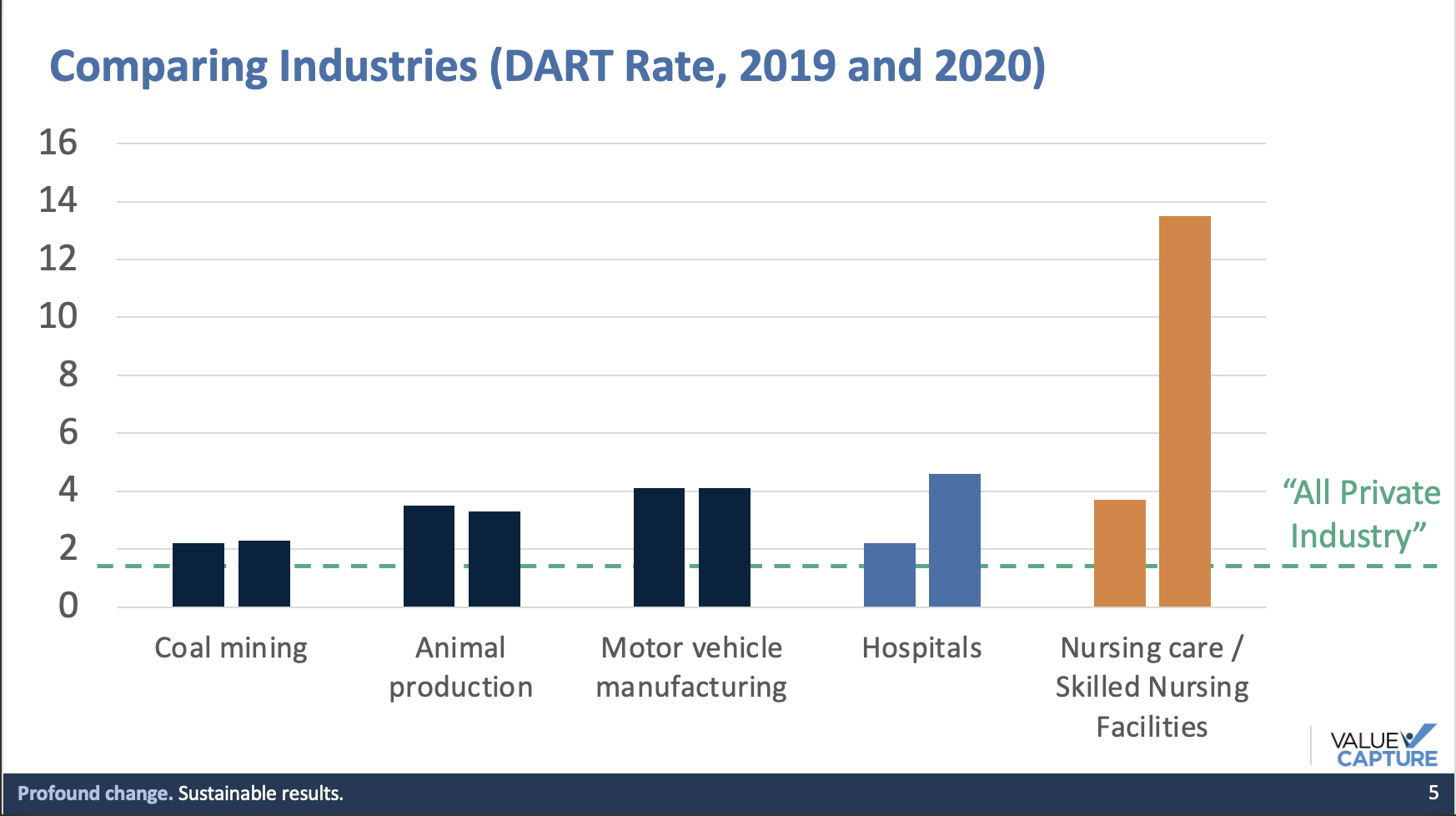

It has injury rates almost twice the rate of private industry as a whole, and that's according to OSHA. And you can learn more at osha.gov/hospitals. It really gives us something to think about. So then one way of measuring employee harm is a measure called DART rate. It's an acronym: days away, restricted or transferred. So we like to ask people, do you know the number for your organization? Do you know your current DART rate? Or do you know a similar measure? Do you know where you would find such data or information? You know, we'd love to hear some of your thoughts or answers to that in the chat.

Mark Graban (4m 37s):

So DART gives us an opportunity to measure and compare, engage progress, and we can quickly compare healthcare against other industries looking at data from both 2019 and 2020. We can further break down as OSHA does healthcare in to hospitals and nursing care or sniff facilities. And we can see even before what's clearly a 2020 covid effect, healthcare still had higher dart rates than this green line, the grand average of all private industry that goes across all sectors. The dart rates in healthcare are higher than industries that people might consider to be dangerous, like coal mining and animal processing.

Mark Graban (5m 21s):

Now, we look at these healthcare numbers on average, but I think it's always important to look at the variation in these numbers as, as some organizations have clearly performed better than others in terms of safety in general and during covid times. So why do hospitals, why do some of them have lowered dart rates than others? It's, it's not luck. It, it comes down to leadership.

Ken Segel (5m 45s):

Thanks, Mark. Mark had a, Mark talked about leadership and you know, Paul matters to me not cause of those high positions of leadership he had, but because of, of what he did with him, what he allowed others to do with him, the inspirational levels of human performance that are possible when people are well led and led by principle and systems thinking. And Paul had a saying that connects the dots here, which is that he believed organizations were either habitually excellent or they were not. You could not be partially excellent, and if you were partially excellent, there was always the worry that the parts of the organization that were not excellent, so gonna overwhelm those that you'd started becoming excellent.

Ken Segel (6m 32s):

He didn't believe in priorities, he believed in Excellence. And he also had a saying, he would say every organization in the, that he had come across had a saying somewhere in their annual reporter elsewhere that people were their most important resource. But there was precious little evidence that it was really true evidence that was created, that people really were valued above anything else. And in some cases, as we know, quite a bit of evidence that that's not true. And for him, it started with workforce safety and then workforce safety and patient safety because that could produce the evidence that it was true. And here's the key point, that the same skills and mindset that were vital for achieving zero harm were exactly those that were acquired for being excellent in everything that you did.

Ken Segel (7m 25s):

So there was that direct connection in his thinking and work. And so we're gonna talk to you about the playbook, we're gonna give you a little more background, and then Mark is gonna walk you through the steps. And one of the things though that we wanna emphasize here is that the playbook is not a cookbook. It is not a, A than B than C than D. It is much more of sort of a principle-based sort of GPS, if you will, that is sort of guides you on the framework that you can apply to any situation that you have and, and drive the organization forward. Although it is very practical, and you'll hear that as we go forward.

Ken Segel (8m 7s):

There's another point we just wanna underline here, which is we hope that the O'Neill framework, and again, collaborated with lots of people and lots of different settings to do this, you'll agree, is quite different from some of the more traditional leader leadership ways of acting and, and sort of getting through crisis. And I'll, and I'll just say, you know, in that we're seeing hints of now, you know, in the contrast of principle based and systems thinking, you know, we see the press is full of reports of our own industry with, shall we say, flexible ethics with regard to some of the vulnerable communities that we serve. And then rumors of layoffs in the face of what are in fact systems challenges and can be solved a different way.

Ken Segel (8m 54s):

So it's a different way, and we hope you'll see that. So why talk about this playbook now, and maybe it's obvious, but you know, what organization is not struggling, does not have people struggling, you know, 60% disengagement rates. We all know in healthcare what we're facing in terms of the workforce crisis and what organization doesn't after what we've gone through in Covid have a need to connect with our workforce in a much deeper way about something that truly matters to 'em about something that brings them back to the great achievements that we were able to do together, sort of driven forward by the crisis itself, but yet we've sort of lost focus.

Ken Segel (9m 39s):

What was it that got us there, etcetera. So we have the workforce concerns and struggles, and then for those of us that have responsibility for guiding the improvement system in our organizations, you know, who hasn't seen a gap open up between where we could be and where we are and wanna fill it. So what's, is there a framework out there that can bring these two things together and sort of drive a rejuvenation innovation moving forward together? We think there's, So right from the start, Paul would say, Paul O'Neill would say, leaders have to have a framework for leading right from the beginning.

Ken Segel (10m 23s):

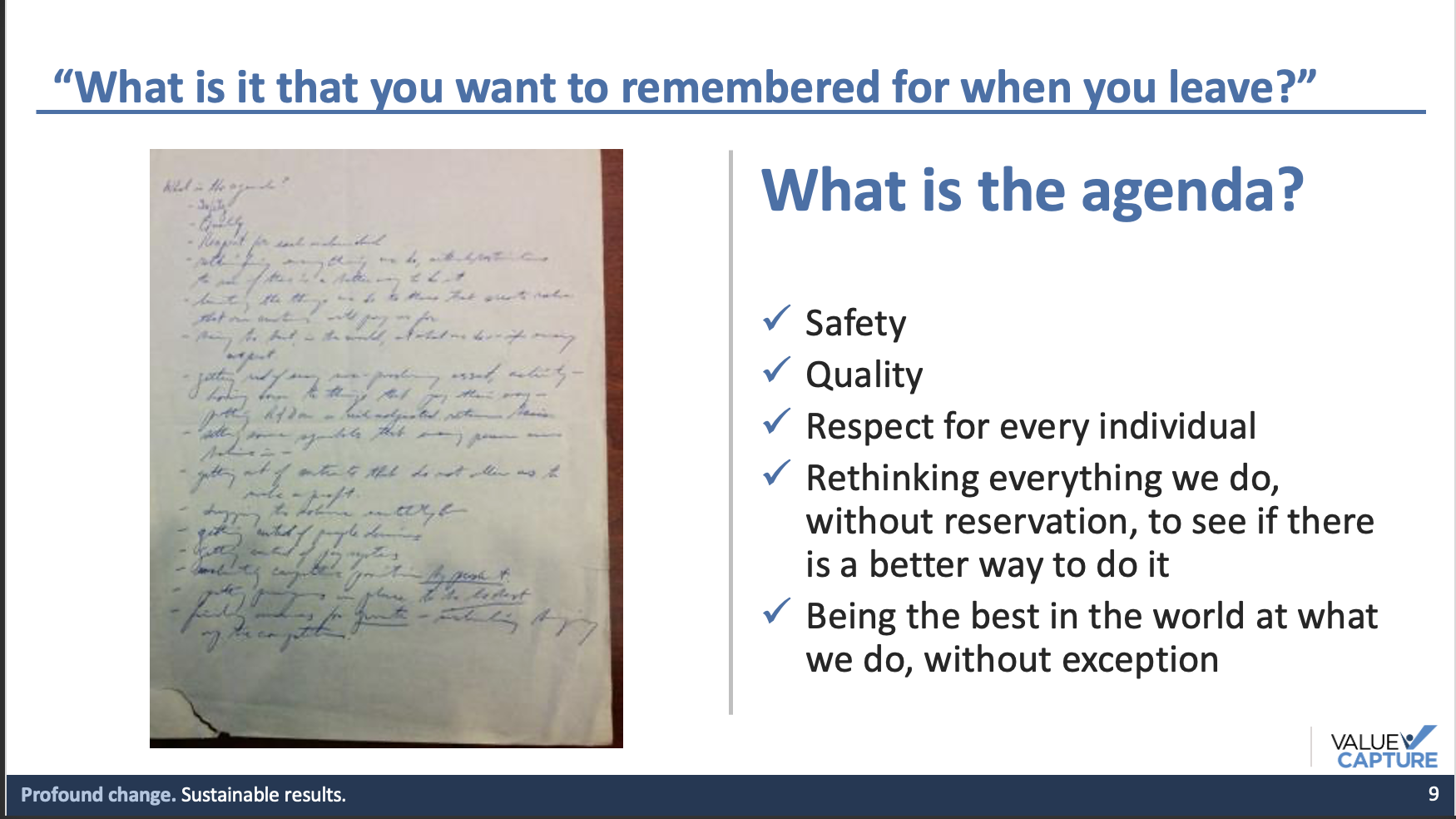

And I'll give you an example, one that really, and look at this anchor at the top. What is it that you wanna be remembered for when you leave the framework? You had to get it, you had to think about, when I am long gone, when I am past this seat by many, many years, what do I want to be remembered for? You know, through the achievements of the people. And I'll give you an example. He had three months before he became the CEO of Alcoa to reflect on from working his way up from the bottom, what leadership mattered to him as a person in the organization, what was good, what was not good, but also talking to the customers of Alcoa, the people of Alcoa.

Ken Segel (11m 4s):

And that all coalesced for him because, you know, what he felt were the key principles sort of met a company at that time that he felt was sort of resting on its laurels despite balance sheet trouble, and was content with being better than average. And so he put down, and on day one when he got to his seat, he had this single sheet of paper that's being displayed here. And he, it, it sort of gave what the agenda was for his entire tenure and he referred to it every day and he kept it in this desk throughout his entire career. So it starts with what is the agenda? We'll just give you a few highlights here. And it starts with safety, quality, respect for every individual.

Ken Segel (11m 47s):

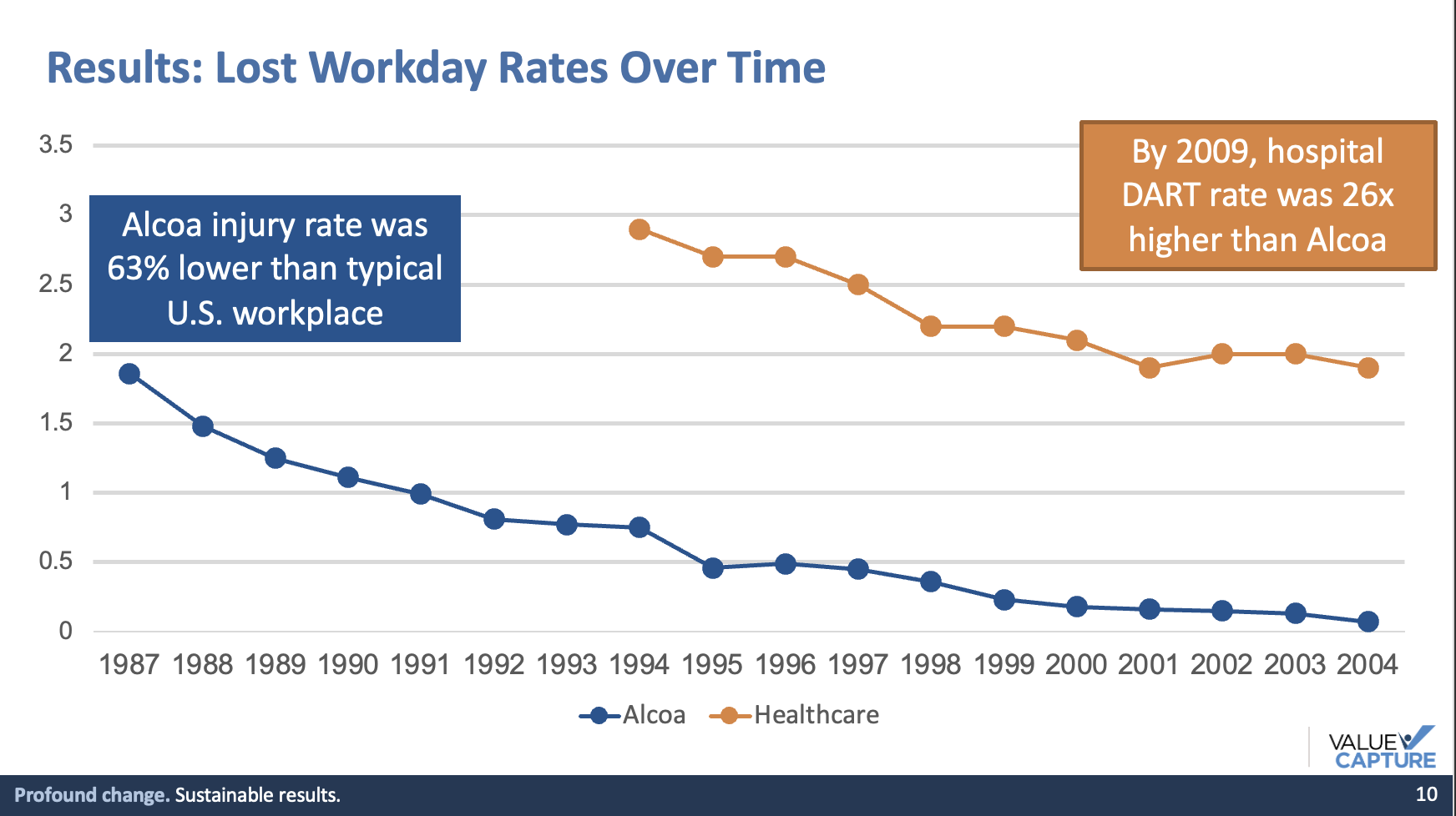

Those are the first things from a Fortune 100 CEO. And then here's this tide to this broader excellence, this case we're making here, rethinking everything we do without reservation to see if there's a better way to do it, and being the best in the world at what we do without exception. So you're not hearing a lot of improvement words, you're not hearing a lot of lean words. If that's your flavor, you're hearing about a larger aspiration, connecting excellence together in plain language that people can identify with. All right, so now let's move on as we, for the slides to advance for, to see what's the evidence. So if safety was the thing and he was gonna lead from safety, what was the evidence at Alcoa and how did they do?

Ken Segel (12m 28s):

So when they started, you'll see the safety record here in terms of the last workday rate, a version of, of what Mark described to you earlier, Alcoa was actually already in the best third of American companies when they, when O'Neill's tenure started in 1987. And they were quite a bit better than that in industrial companies. And so the sort of that the new goal was zero was quite a shock to them. But you see there, you see their progress here. Now, just to compare to our industry, for those that don't know, here's our curve along many of the same years, and by the time O'Neil left as CEO in 2000, he left in 2000 and then a few years after Alcoa was actually 26 times safer to work in despite a truly terrifying industrial environment in most of its plants and locations than our, our own healthcare facilities.

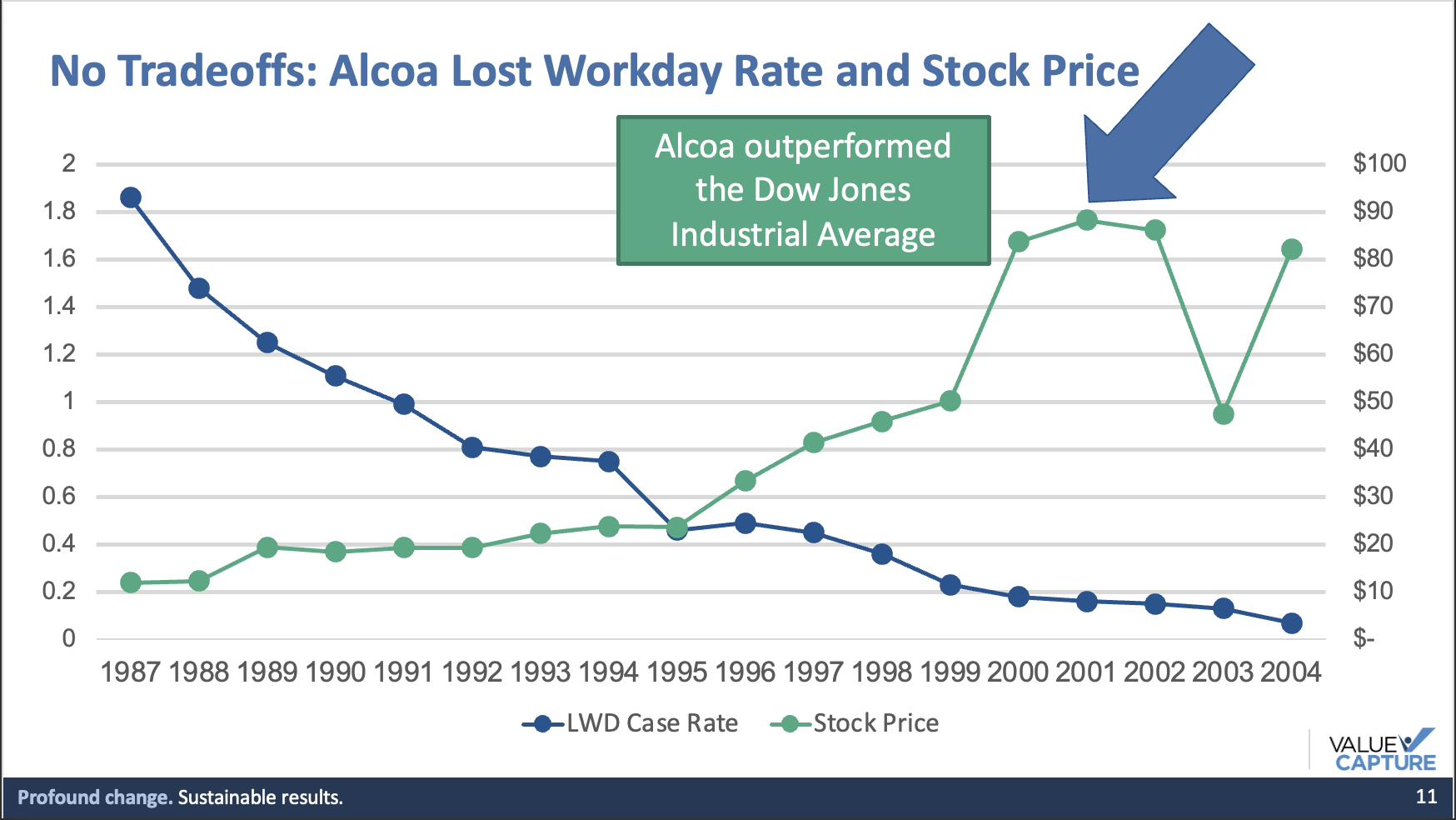

Ken Segel (13m 20s):

Sobering. So the question a lot of leaders have is, was there a tradeoff in terms of financial performance? Were we overemphasizing something at the extent of others? And, and Paul would argue quite the contrary. And so there's the safety record and in a second here we're gonna pop up the actual stock price at Alcoa. And remember 2000 is when Paul left, you'll see an arrow pop in here and they outperformed the Dow industrials during this time of, of growth. So they outperformed other people and their market cap, they were growing crazily as their outperformance allowed them to take more market share and grow across the world. So they grew by 900% during this time.

Ken Segel (14m 1s):

So not a, not a trade off at all, no trade off thinking. This is a key thing that we say. And so then there's this other crucial element, sustained safety performance. So Paul would say a leader's true. In fact, this won't surprise you once you saw the framework is measured by long after they're gone. So if the rate continues to leave, I will have been a success. So let's look at what that curve looks like. So right in the middle of this graph, 2000 is when Paul left and you can see the bump. There was a questioning in the organization in some big acquisitions then is this gonna be real? And then the subsequent leaders kept it going, driving towards zero. So again, that that, you know, we're really trying to hit the sustained excellence, the habitual excellence element of this.

Ken Segel (14m 47s):

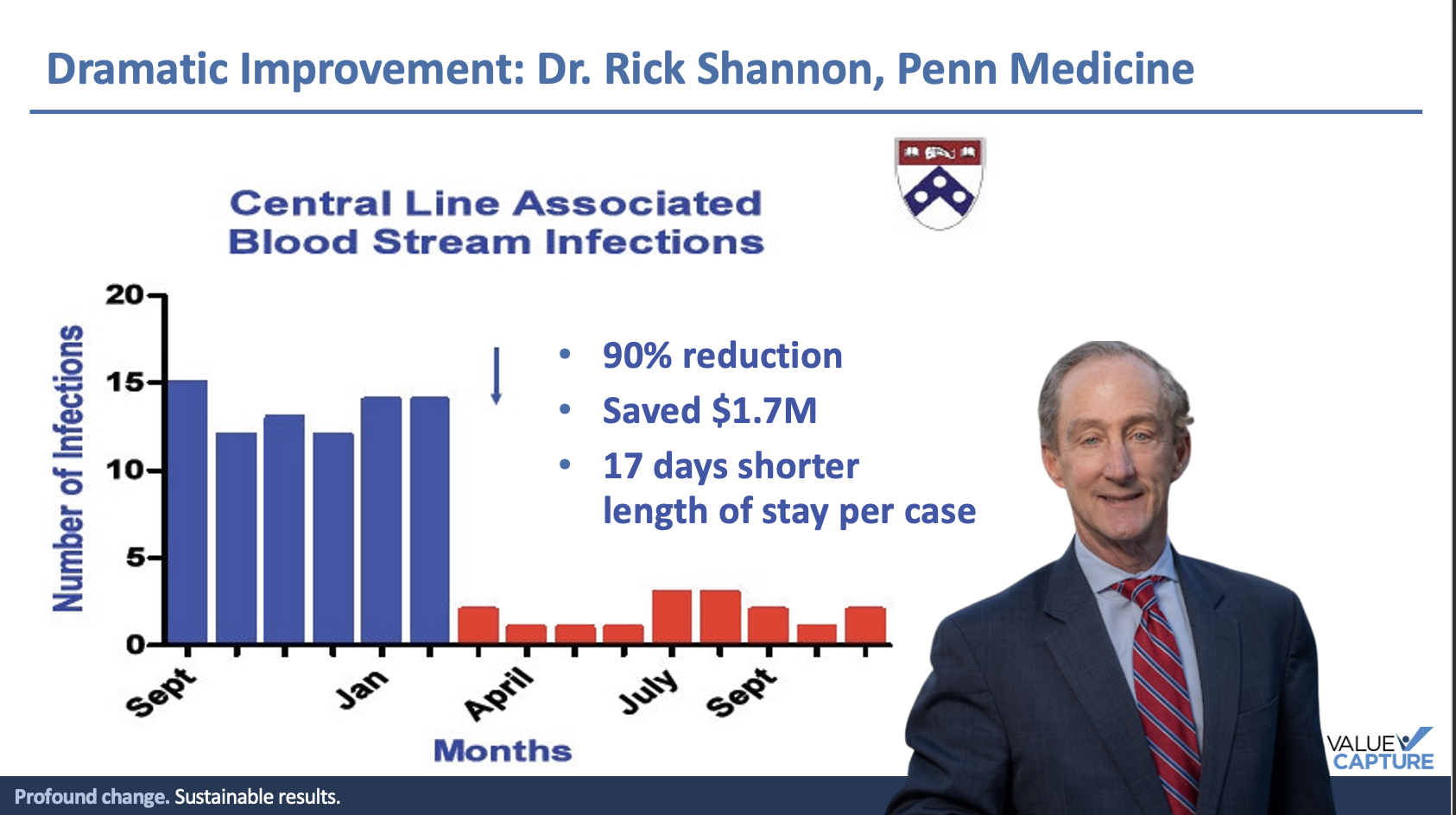

So, okay, but that's industry where healthcare can it translate to healthcare. So can we get the same dramatic improvement? So here is Dr. Rick Shannon, who started as Chief Medical Officer at a large system here with us in western Pennsylvania, working with our colleagues from CDC and others and applied the O'Neill framework toward a set of healthcare-associated conditions. We all know that at the time he took over his set of ICUs were bubbling along at a, a rate that was accepted, thought people thought it was the best we could do, applied the framework and let's look at what the results are here. Pretty dramatic down. And when you do the right thing for quality and safety, guess what? People get through the hospital faster, they, a lot of money is saved and money that fell to the bottom line of the institution.

Ken Segel (15m 34s):

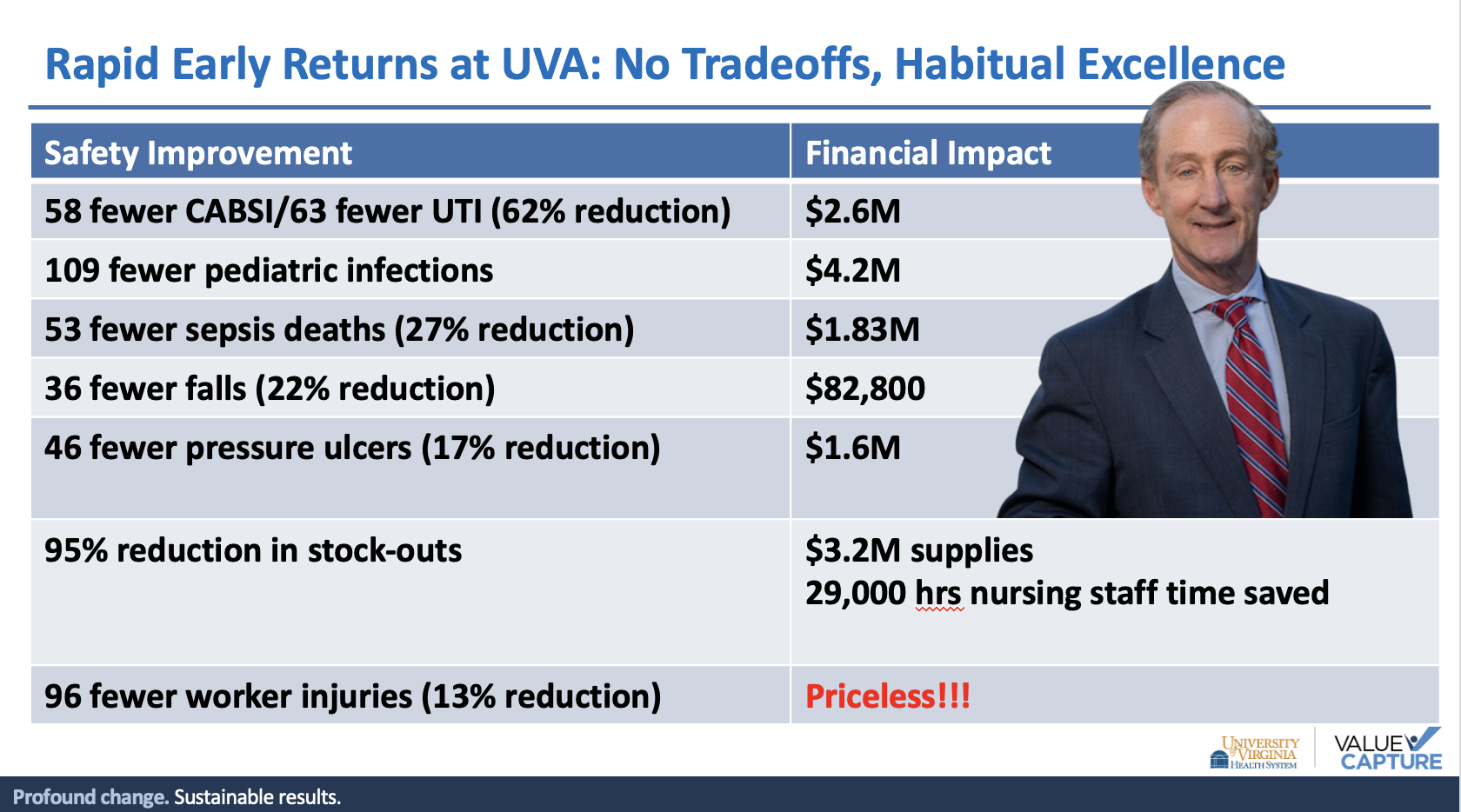

Okay? But that's, that's in half of an inpatient setting. What about when you get to a whole health system? So here are some of the early returns at the University of Virginia Medical Center across the whole system from about a year's worth of work putting in place the O'Neill framework. And you see dramatic improvements in patient safety at the top with correlating fiscal benefit. And then you see this wonderful stuff of both the workforce safety, you know, the priceless gains there because you're doing it together, keeping our people safe to keep the patients safe, but also this connection to the workflows themselves, the stockouts, the customer-supplier relationships, the excellence in all things it's happening.

Ken Segel (16m 15s):

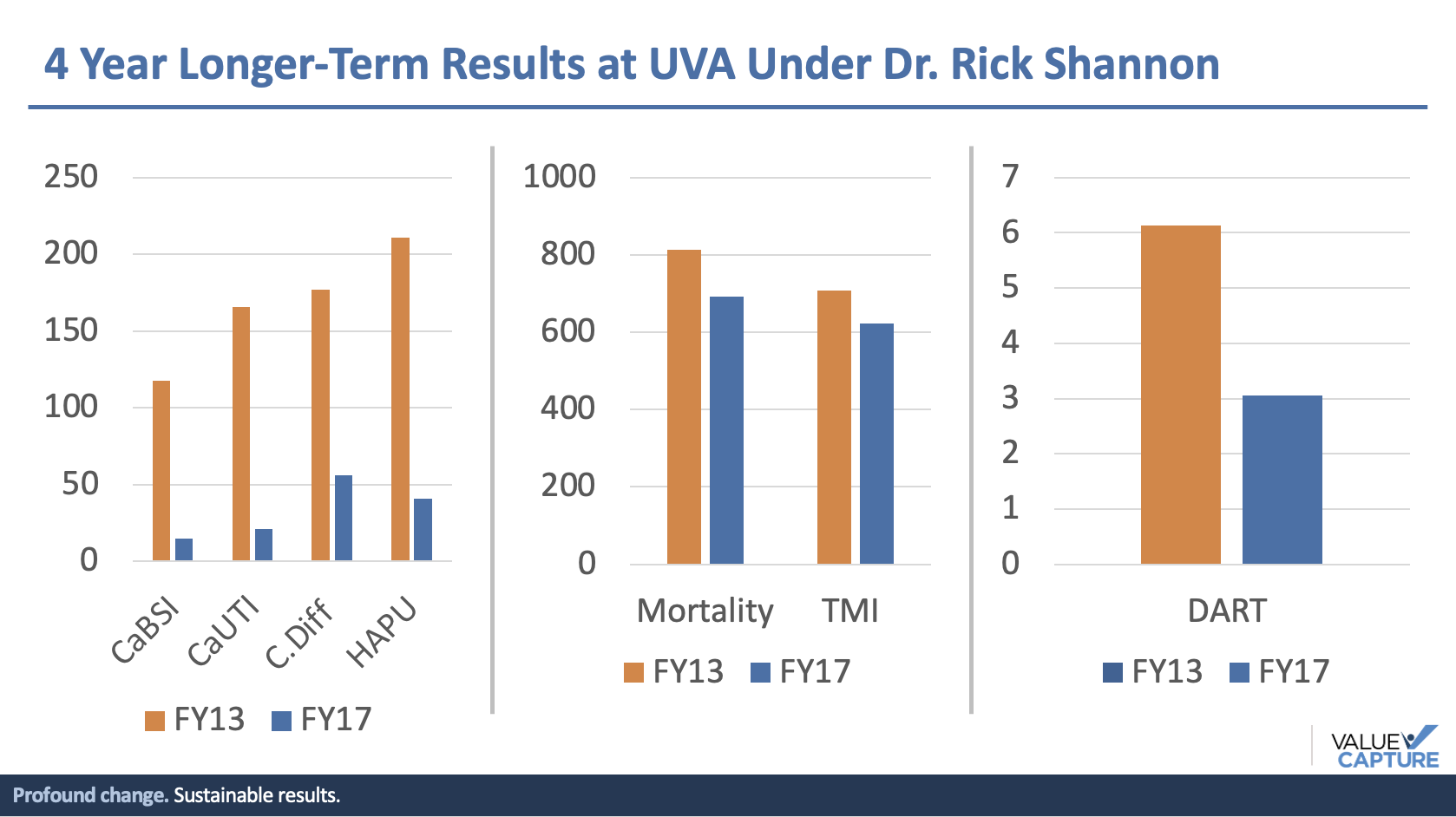

Oh, and reminder who, so who was the leader of this? It was, it was Rick Shannon who had gone to become the vice president of the entire university overall, the health sciences. So it's applying at scale here. One example among many and our, and our industry as well. But let's look even further four year results under Dr. Shannon and his colleagues in nursing and across the whole enterprise because I think this is where that the notion of enduring excellence comes in play. So you see that 90% plus drops in our common categories of, of healthcare associated challenges. And then look at this despite growing volume and you know, in our, in a in a sicker patient base, the actual numbers of mortality are going down.

Ken Segel (16m 58s):

The, the TMI incidents that, you know, the early indicators, the predictive indicators of things going wrong later in the hospital stay are actually following despite, you know, sicker patients. And so the care is clearly improving. And then look at this, here's the workforce safety rate falling in half over four years and, you know, and continuing to improve. And by the way, FY '17 was their best financial year ever.

All right, so could it even apply in government? So here's Paul O'Neill, your first snippet of Paul saying, you know, if anybody expected him to not try to apply the same ideas in government, you, you didn't know Paul. So here's, here's his, here's his answer:

Paul O'Neill (17m 37s):

The injury rate at the treasury was unbelievable. In 23 months, we reduced the injury rate at the treasury by 50% in 23 months.

Ken Segel (17m 49s):

So he, so he led with safety. Again, a lot of people don't realize treasury has a lot of actually dangerous departments in it and including the US Mint. And so he led with safety, but it's not just about safety. And this, again, we're trying to make this connection to excellence in all things, to being successful in all things. And, and to introduce that here is Paul talking about a challenge he gave to his controller because he wanted the same ideas about safety for people to realize these are principles for approaching problems and challenges and, and the opportunity to add value in the organization that applied to everybody and that they could do no matter what their work is. And so he gives his controller a challenge as to in the ideal, how close could we, how fast could we close the books at the end of each quarter?

Ken Segel (18m 38s):

And you'll hear how that plays out. And I'll make a couple comments after,

Paul O'Neill (18m 41s):

If we had no repair work and all of the time that we spent was high value touch time, that means we're actually producing value in every minute of every day. How long would it take? And about three weeks, he came back to me and he said, I've figured out the answer to your question. And here it is right now we're closing the books in 11 days. If we did it perfectly, we could do it in three days. And I said, you know, Ernie, that's our new goal. And he said, No, no, that's not what I meant. Oh my God, we can't really do that. That's just the answer to your question. I said, Hey Ernie, we're trying to be perfect at everything else we do, including workplace safety.

Paul O'Neill (19m 22s):

And in a year we got the point where we could close our books in three days. Full stop. This is not about firing people, it's about creating the opportunity for applying resources in a way that produces ever greater value.

Ken Segel (19m 41s):

And that's that crucial thing. And, and Alcoa still today reports the results earlier than any other company. And what that was doing was giving a thousand people in finance eight days back every quarter where they could do value-added work instead of repair work. And I'll give an example later in the webinar about exactly the opportunity that we see on some of the current major challenges in healthcare. But we want you to be getting that connection as you go to broad excellence, not just safety. Thank you.

Mark Graban (20m 11s):

Well, thank you Ken. So I want to share some of the, the key principles and actions that come from what we call the Polone playbook. We published a book here, you can get it as a free ebook on our website, A Playbook for Habitual Excellence. And I wanna share some of the thoughts that, you know, that we've summarized the themes that that, that Mr. O'Neill shared. The book is a collection of transcripts from speeches that he gave to different audience, mostly healthcare audiences. And like Ken said, this is not a 42-step program, it, but there are certain things that should be done early, if not first. And, and when we think of that in terms of laying the foundation, and it's not even so much about what to do, it's as much about how you go about it.

Mark Graban (20m 60s):

You know, the, the, the, what we need to do needs to be set on the foundation of, of how we are who we lead, if not who you are as a person, What do you believe? So again, it's a principles-based approach to achieving goals and excellence. And a lot of it starts with modeling the behavior, starting right with him as the CEO. Now, as Ken showed you on his handwritten notes for Mr. O'Neill, respect was very high on that list. It's a word we use a lot in the lean community. We hear similar language from Toyota who was one influence on Mr. O'Neill Toyota talks about respect for people, the Shingo Institute, who we are proud to partner with at Value Capture states it in the same language, respect every individual and like a very actionable, practical, not conceptual way.

Mark Graban (21m 52s):

So what does respect lead to? Mr. O'Neill would quite often say that an organization has the potential for greatness when everyone can answer yes to three questions without reservation. And I think these are powerful questions. First off, am I treated with dignity and respect by everyone I encounter? So he's using words like everyone, you know, everywhere. He would sometimes list what he called distinguishing characteristics as he called them that everybody needed to be treated with dignity without respect to race, gender, rank, education. I mean, he said any other characteristics.

Mark Graban (22m 32s):

So he means everyone. And, and then he asked another I think is, is if that first question's not powerful enough, am I given the resources I need to make a contribution to the organization that adds meaning to my life, right? How many organizations would stop with the contribution to the organization part, like looking for this alignment of, of this connection, this feeling, this need we all have to contribute to something bigger than ourselves to be part of something excellent. And then thirdly, is my work recognized by someone whose opinion matters to me?

Mark Graban (23m 12s):

And not like in a, a superficial way, but like, are you really? And it could be a small moment of recognition of somebody saying, thank you, you did a great job there. It doesn't have to be anything with a whole lot of theatrics or formality. And, and so from this foundation of respect, there's another phrase of his I love. He says, Leadership is all about obligation and nothing about privilege. The obligation of leaders. This sounds like servant leader language, where he would say leaders are personally responsible for everything that goes on in their facility, including, most importantly, for everything gone wrong.

Mark Graban (23m 53s):

He took personal responsibility. When he shared the story of talking about learning about the first death that occurred to an employee at Alcoa under his watch, he used very direct language to, to take responsibility of, of in, in, in the video he says, We killed him. I mean, I killed him. Like that sense of obligation responsibility is, is really powerful. One element of of respect, you know, is kind of breaking down traditional hierarchies or, or symbols of rank or privilege to create what you might describe as a more egalitarian culture. And you know, research shows that when you know, the shingle principle of respect for every individual is really held to, that's a huge driver of team member energy and productivity.

Mark Graban (24m 43s):

So there are stories from his time as CEO very early on asking, you know, why are we buying coffee and the business paper and danish for our executives is, do we provide that to everybody? Well, the answer was no. And I think he said, Well, we, we can pay for that. Selling off the corporate jet on his first day before lunch poll forced the most exclusive country club in the Pittsburgh region to end exclusionary policies about not admitting black members or women before he would allow Alcoa executives to re-up their memberships. Again, that was part of his agenda on day one.

Mark Graban (25m 23s):

And we had stepped back and think, okay, well our health system might not have a private jet, but what other symbols of rank and status and privilege are there that that maybe interfere with collaboration and teamwork? It could be a physician lounge if, if that still exists or more, more commonly the physician parking the best parking spots going to the physicians. What message does that send? What impact does that have? But coming back to setting goals around safety and reducing harm and, and things like that, Mr. O'Neill would talk about, you know, everybody has a role to play in improvement here, but there are only some things that the leader, or in some cases the CEO can be the one to do

Paul O'Neill (26m 5s):

This can't be done. You, this cannot be a delegated function. You can't have a person who's the vice president for goals. The leader needs to articulate the goals. Other people do not have the power for the position to do that.

Mark Graban (26m 23s):

And so to me, this sounds like, you know, language, you might hear from other settings of the leader setting the goal, but then working with the team to figure out how to accomplish it. He was not dictating in a top down way how to do everything, but there are certain what he would call unarguable goals when articulated and, and combined with other principles that will help guide the way and drive progress. So the first thing that he declared in terms of goals is nobody should get hurt at work. And, and, and this isn't just about a slogan or posters, people would see right through that. It's, it's an unarguable goal. He would say it's the only defensible goal.

Mark Graban (27m 4s):

And, and it it, it's used as a rallying cry for the organization and with some initial action to turn words into reality. Word spreads in a very positive way and we can build momentum. People can see we're serious. And a different way of, of stating, you know, this idea of safety is a precondition. He would, he would say safety is like breathing. And I think, you know, breathing is a precondition for Ken and, and for me to be even giving this presentation today. And we don't stop and think about that very much. I'm thankful to be breathing, but you know, safety is that precondition for doing anything else. It should be just, it, it should be embedded into how we do things.

Mark Graban (27m 48s):

So he would talk about zero harm to employees and then more broadly you can talk about setting goals at the theoretical limits of performance. And then you have to do the work, right? It's not about just setting goals or trying to just inspire people. We've gotta do the work. Mr. O'Neill would say, you know, if God doesn't prevent us from doing it via the laws of physics, we can do it. If that means a three day closing of the books at Alcoa or if that means working towards zero harm in a unit within a hospital. But again, the supplies, this theoretical limits thinking applies not just to safety but to all performance. How do we aim to be the best at getting better?

Mark Graban (28m 30s):

As Dr. Rick Shannon puts it, our goals at the theoretical limit tend to be zero or a hundred percent. So we hope a hundred percent of you are enjoying and getting something out of the webinar. That is certainly our goal here today. Let's hear a little more from Mr. O'Neill.

Paul O'Neill (28m 46s):

It's within the capacity of leaders to articulate a zero goal and then to accomplish. And I'm gonna tell you a little bit about how do you accomplish it because it's not good enough. Cheerleading won't, cheerleading won't do it.

Mark Graban (29m 5s):

It's not a matter of cheerleading, right? It's about sustained leadership. And, and one leader who's been inspired by Mr. O'Neill and, and Rick Shannon and others is Rhonda Brandon from Duke Health. She's the chief human resources officer. And as, as she said in a podcast interview we did with her, we've created a mission or an aspiration of zero harm, zero harm for our patients and each other. Aiming high is not enough. There needs to be intentional focused and collective drive towards excellence. So there's some other principles and practices and ideas that Mr. O'Neill shared that I think are very transferable today. Now one, you know, we start getting into, you know, the question of language.

Mark Graban (29m 47s):

He would say, stop using the word accident. He would say the word accident makes it sound like it was something God intended to happen. It's inevitable. It just, you know, he would say, use the word incident, right? And so when, when we talk about not just the goal of zero accidents or zero incidents, so it opens this conversation around not accepting what has been and instead working to improve and, and, and work towards zero. Now from kind of a practical finance perspective, I think this is interesting. He would say, Don't budget for safety improvement. Wait, what? Well, he's not saying don't spend money to improve safety. He's saying change the way that it's framed.

Paul O'Neill (30m 28s):

We're not gonna have a budget line for safety as soon as we identify anything. As soon as anyone in the institution identifies anything that could cause an individual to be hurt, we're gonna fix it and we're gonna fix it as fast as it's physically possible.

Mark Graban (30m 52s):

So again, he would say safety is a precondition, not a priority. He would tell his finance staff that they would be fired if they calculated the cost savings from safety improvement because he said that that would remove his moral, you know, kind of leverage or standing on the issue that this was the right thing to do. And then occasionally in healthcare you do see, you know, this pretty direct language like we heard from Paul O'Neill, Jim Conway, who was formerly the COO at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, said, and again, very blunt direct language, after we killed Betsy Lehman, a famous case, Boston Globe report, in some ways we spent far more than our budget on safety and in some ways far less so.

Mark Graban (31m 40s):

You know, he, he was, you know, you, you get so much more out of doing this. It it's, it's not just about the money. You're not gonna bankrupt yourself by doing what it takes to improve safety and to prevent harm. Mr. O'Neill would say, you know, leaders need to go to where the work is done and make certain key commitments. So these are stories he would tell about being at a factory in Tennessee.

Paul O'Neill (32m 3s):

And then I turned to the hourly workforce and I said to them, You heard my instruction to them. Here's what I wanna do with you. I want to give you my home phone number so that if they don't do what I said, you can call me. Not many CEOs were giving their home phone number away.

Mark Graban (32m 23s):

So a modern adaptation or that might be to give your cell phone number out or you know, send me a slack message. I don't know what different ways to do this. But, but the point is to open that chain of communication if the safety commitment is not being met locally after Mr. O'Neill had made that he hoped clear to local plant leadership. But what, what happens after somebody reaches out?

Paul O'Neill (32m 48s):

And after I had to make a couple of interventions, I didn't have to make any more interventions.

Mark Graban (32m 53s):

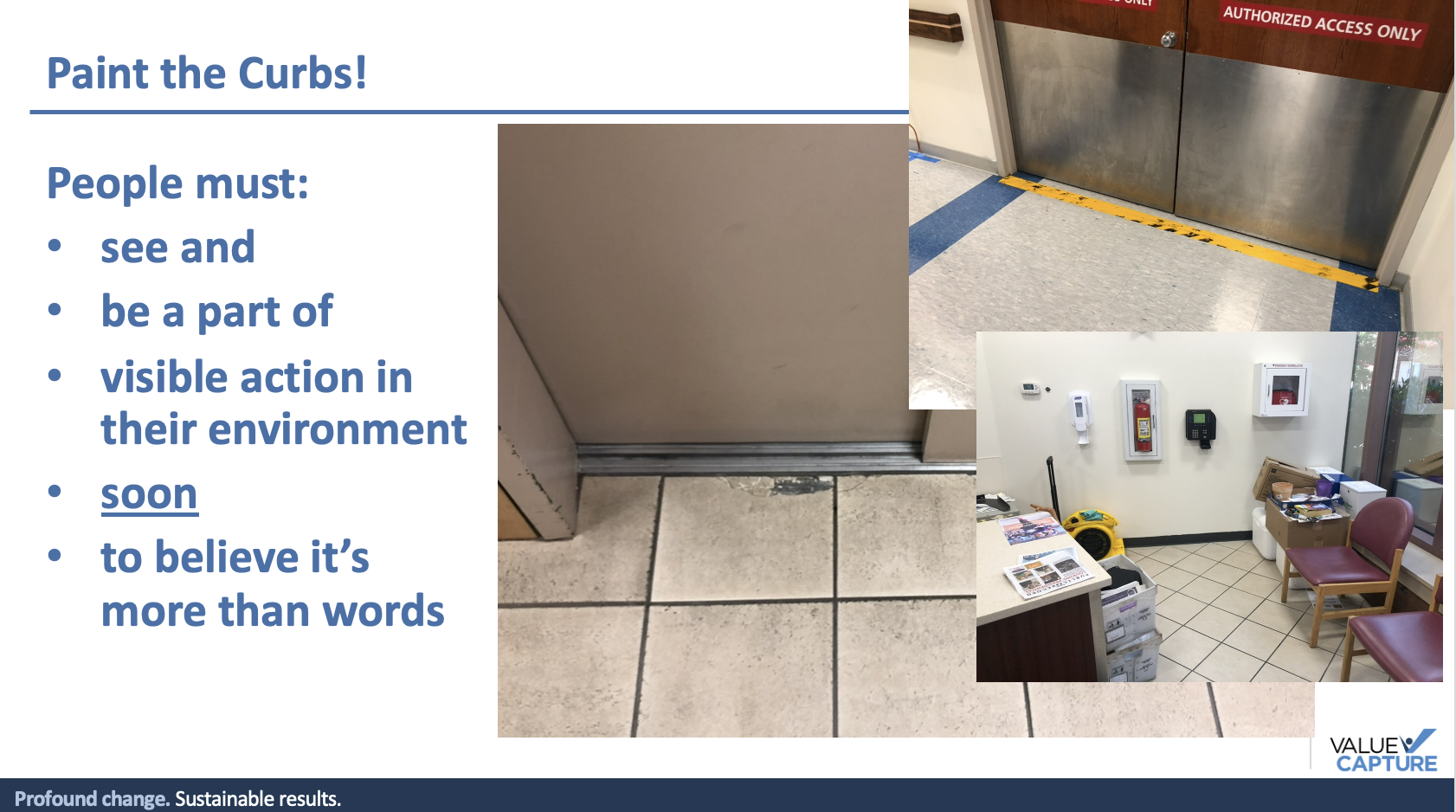

Cause I think leaders and people through the organization, the message finally gets through, the words have been followed up by action. He's serious about this. We are going to fix safety problems and better yet be proactive about preventing safety problems. And he would emphasize, you know, when you get that first phone call and he did thank the employee for speaking up about it and then follow up immediately with the plant, not in, you know, this overly punitive way, but just to remind people, this is a precondition to focus first on safety. He would say, you know, for example, you know, once you solve these goals and expectations, you need to make sure that there are some really visible actions that you're painting the curbs, if you will.

Mark Graban (33m 36s):

And, and this can reply to, this can apply to taking visible action around safety risks in, in healthcare. If staff are saying we need a certain type of, of needle with a cap, get that like something very visible and, and word will spread, people need to see and be part of visible changes in their environment. And a lot of this can come down even to just the level of pride that we have in our workplace. Walking around with staff and, and, and, and looking at things that the public would see, that staff would see broken tiles, you know, kind of faded safety lines in front of an operating room. Access piles of clutter in a waiting room that I guess we've just stopped seeing.

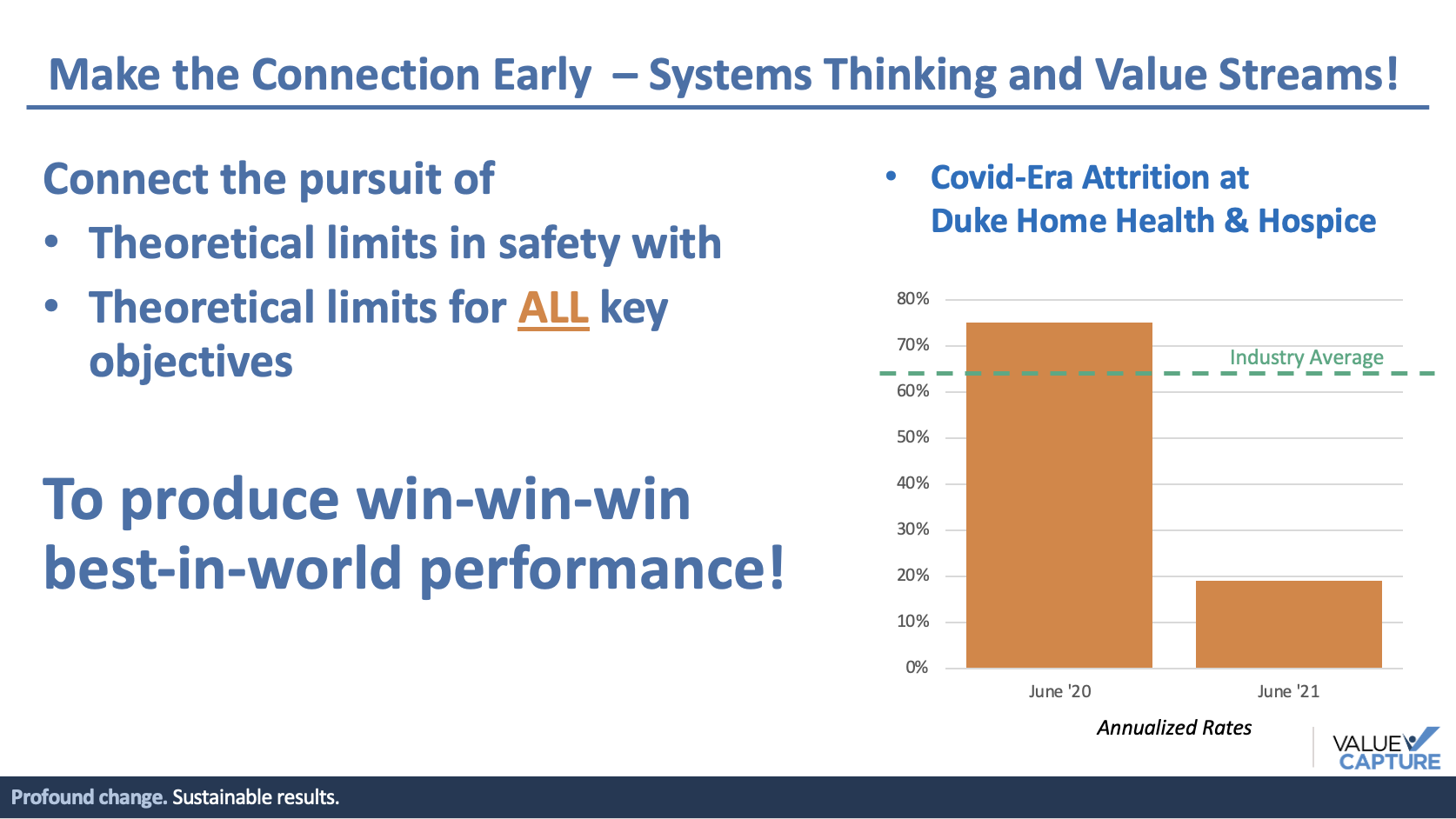

Mark Graban (34m 20s):

And, and, and to, not to shame people over this, but to, to, to make a commitment that we can fix these things as a very visible manifestation of our goal of improvement, if not excellence. And we wanna make the connection early between not just point improvements, but systems thinking and value streams. So we wanna connect the pursuit of the theoretical limits and safety performance to the theoretical limits of all key objectives to really try to get best in world performance. And they have one example recently from an organization that we worked with, even during the Covid era at Duke HomeCare and Hospice.

Mark Graban (35m 1s):

They reduced their annualized turnover rates from above the industry average. They were at about 75% down to under 20%. And it wasn't a magic program. It wasn't all about pay, it was about this very visible, consistent effort to take care of the employees, to give them what they need, to let them answer the three questions that we referred to earlier. Mr. O'Neill, you know, even, you know, think, you know as a, as a, you know, older man standing up on stage reminding us to ask questions like a third grader. And, and, and there were many stories of, of him doing this.

Mark Graban (35m 42s):

Learn to ask questions like a third grader, he would say, they will ask questions that are a lot harder than adults will ever ask you. They're they're questions of, of innocence, of asking, you know, why do we expect to have a certain number of infections or falls every year? Why, why do we assume that that has to be the case? Why is this happening? This is fundamental to lean thinking, this idea of questioning and challenging everything. And you know, we, we can ask ourselves as leaders, do we do this? Do we encourage it? Do we model and reward these behaviors of, of being inquisitive? Again, not to put people on the spot, but to, to really help people open their eyes about what's possible and what we're going to do.

Mark Graban (36m 27s):

Mr. O'Neill would also say, we need to take away excuses. Taking away the excuses that, that people would throw out there of why we can't reach zero or why we can't be best in the world at what we do. And, and these excuses tend to be the same in other industries. People would say, Well, you know, it's not possible. We, we could say, Well, we haven't figured out how to do it yet. You know, it's not in the budget. Well, let's not let budget be an issue. People say, you know, people aren't perfect. Human error is inevitable. Like, well, we're not perfect, but that's why we need to build better systems that protect workers and patients from the possibility of being able to do something wrong.

Mark Graban (37m 10s):

So instead of tolerating excuses, instead of making excuses, what can we do to help take excuses out of the way? And you would also say, you know, in some, again, interesting phrasing, look for the dark places where the values aren't true. That he knew organizations rarely improved at the same rate everywhere in the organization. So he'd say, leaders need to actively look for parts of the organization where the values aren't being lived or they're not being fully acted upon yet. Go look for the dark places and, and, and give the lie to what you're trying to do. He, there's a famous story of, you know, one business unit at Alcoa who was suppressing safety reports.

Mark Graban (37m 53s):

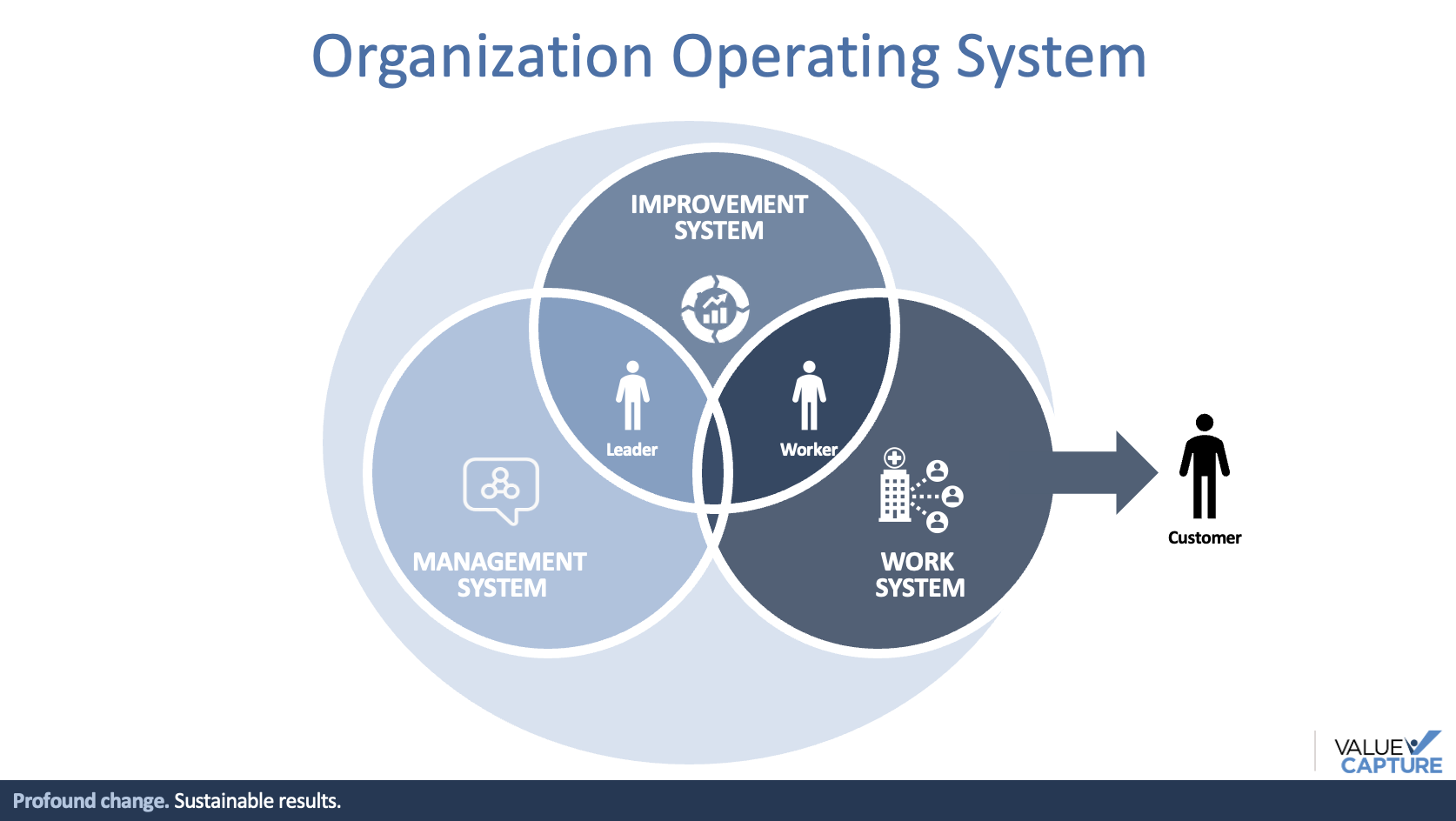

So it was violating one of the fundamental principles at Alcoa. And that leader was let go in spite of their financial success. And, and, and this principle can also mean going to where your least privileged teams work and, and look at their working conditions, asking yourself hard questions and again, following through. So we lay the foundations, we we focus on principles and we need to build and drive systems and behaviors to make this true. Again, it's not just about audacious goals or inspiring goals. It it's about the leadership. It's about building systems or the three systems that we talk about. There's the work system.

Mark Graban (38m 33s):

How is the work structured and executed? There's the improvement system of how do we improve this work. And then there's the management system. These are three systems that work together. They can be designed intentionally and they can be improved. Mr. O'Neill would say, we need to insist on root cause problem solving. Let's not duct tape the parking lot. Don't paper over problems there. There's a tendency in healthcare and people are doing the best they can in their current environment. We tend to come up with work around solutions that then tend to become permanent. We need to make sure that we're, we're getting to root cause that we're improving the system in a systematic way when it comes to data.

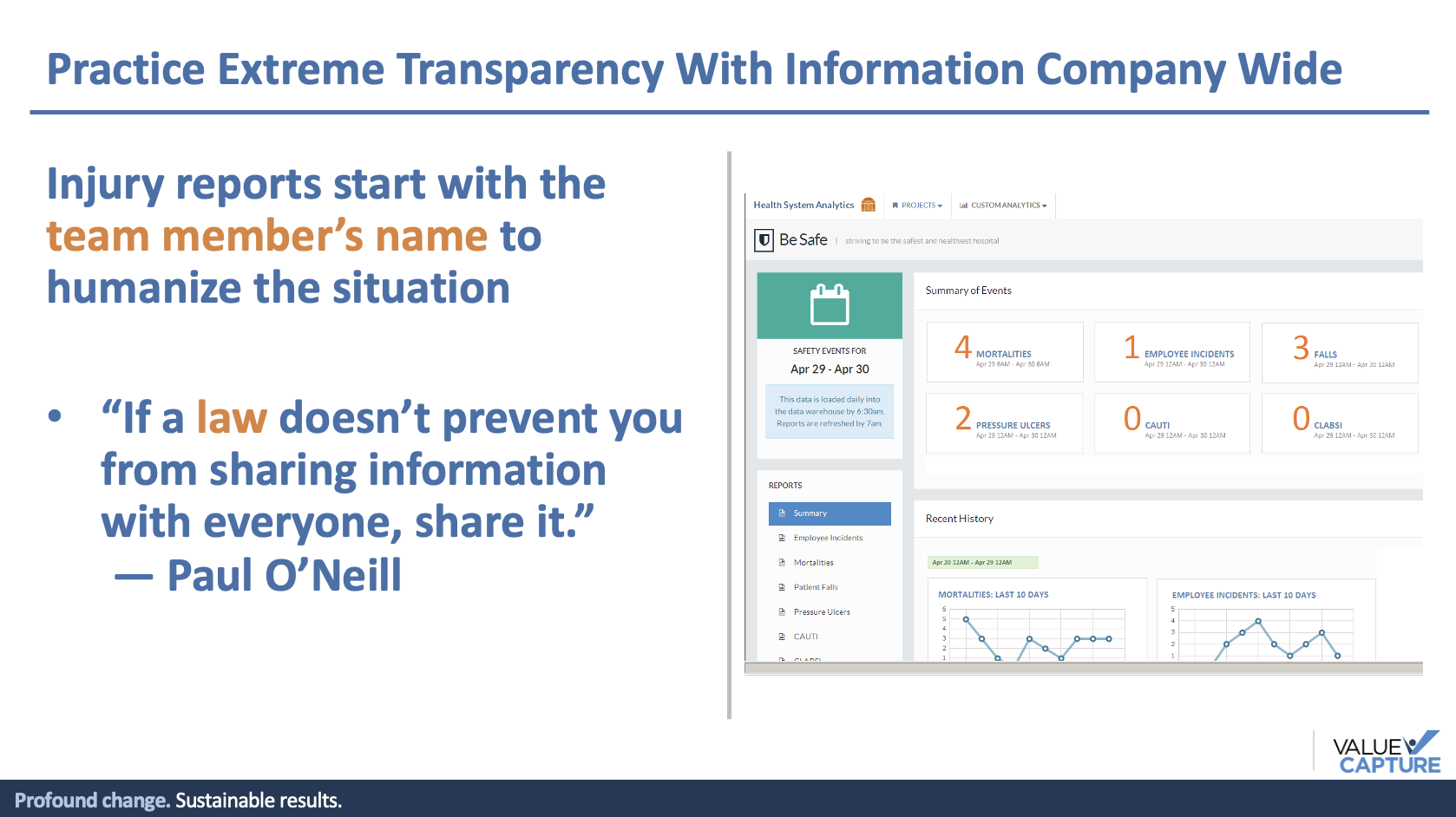

Mark Graban (39m 17s):

Mr. O'Neill would say, you know, we need to establish a real-time safety information system. And they were doing this before the heyday of the internet where you would say, you know, that every injury needs to be identified, investigated, recorded, and shared within 24 hours. And solutions are recorded and shared within 48 hours. We do a better job of investigating the real reality when knowledge and information is fresh. Cliff Orme, who worked is president at International Hospital Corporation, said, you know, what he learned from Poly Neil and from value capture was to take everything gone wrong and solve it in real time.

Mark Graban (40m 0s):

We also always talk about see a problem, solve a problem, share what you've learned, see, solve,

Paul O'Neill (40m 6s):

And where it's possible to do it in 24 hours. The root cause analysis and an indication of a corrective action that's being taken so that this set of circumstances will never again produce this result.

Mark Graban (40m 20s):

Solving problems to root means we prevent reocurrence of the problem. Couple of final points. He, he would, he would say that we need to practice extreme transparency with information company-wide. And COA actually shared quite a lot publicly that most companies wouldn't share at Alcoa. Injury reports started with a team member's name, not an employee number to help humanize the situation, to put names and, and remind people that this is not data. It's people who would say, if a law doesn't prevent you from sharing information with everyone, share it. And there are, you know, different ways on, on intranets or through web platforms.

Mark Graban (40m 60s):

We have technologies that are far better than what he had during his time at Alcoa. We, we can push people on transparency because it, it leads to faster learning. You're not really hiding anything. People know the real reality in the workplace, not sharing the data doesn't convince people that the workplace is safe. And he would publish and Alcoa would publish employee and customer injury data publicly. And there's a lesson here about stating metrics and ways that are easy to understand. And, and Rick Shannon's data was an example of this, of, of not something esoteric like, well, you know, the rate of infections per thousand line days. You can see that chart that Ken showed earlier was the number of infections, if something is countable, count it instead of turning it into a ratio.

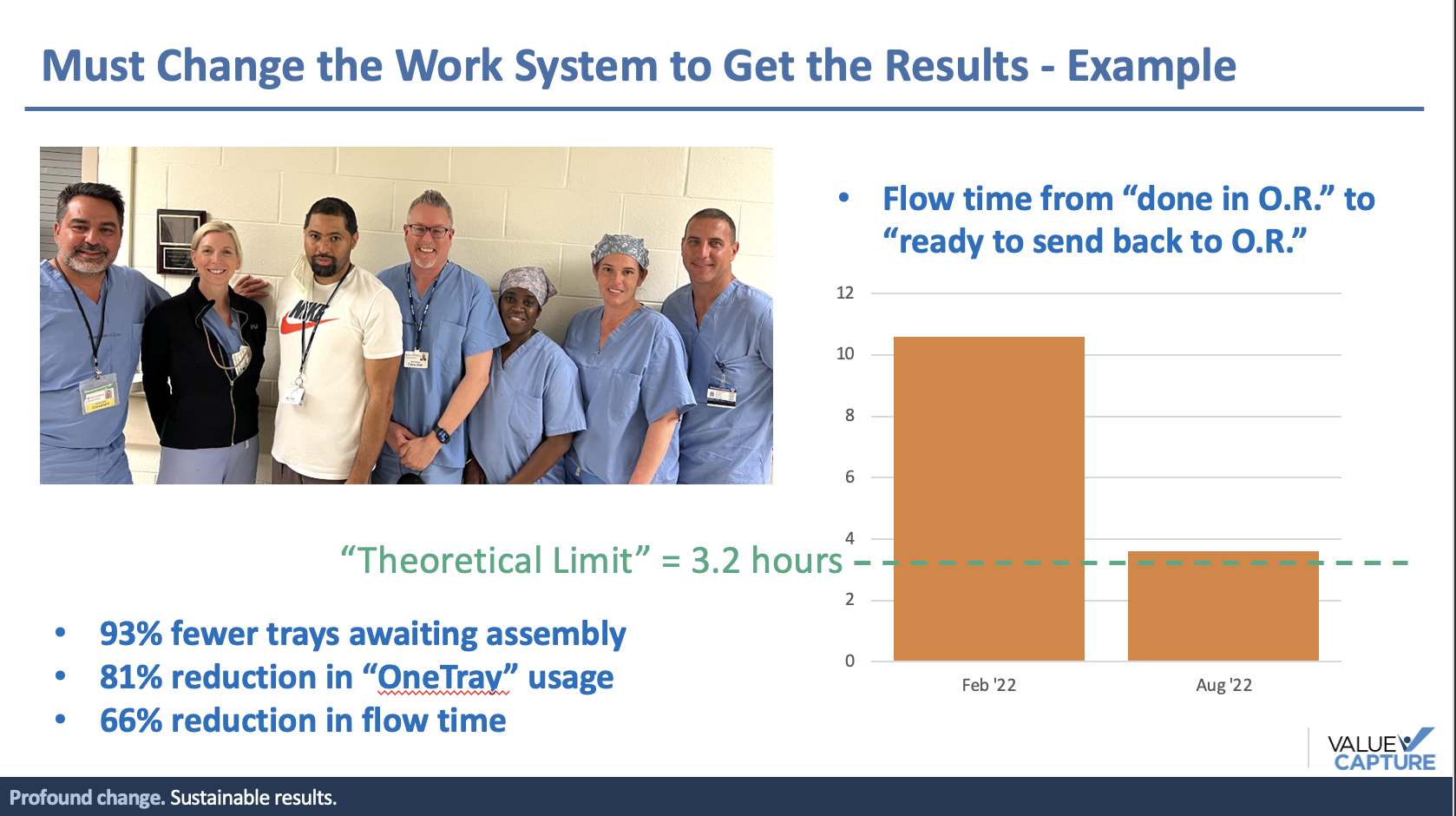

Mark Graban (41m 49s):

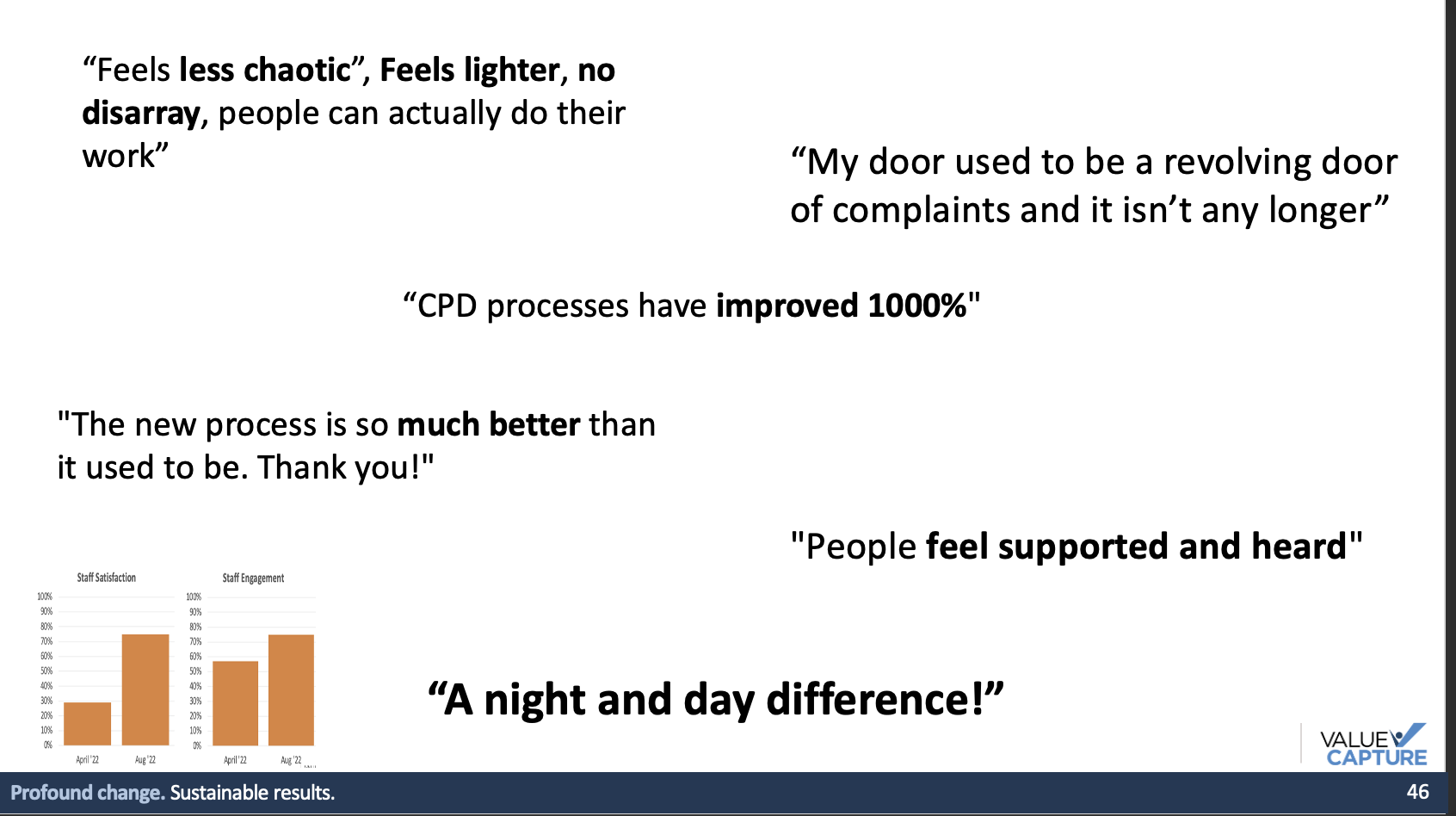

And then I'm gonna share just a real quick example of some work I was able to be part of earlier this year with one of our clients of this idea that emphasizes what Mr. O'Neill said around we, we have to change the work system to get better results. And so here's a team that some of us from value capture worked with frontline staff from operating rooms and, and CPD. And over a course of a couple of months, you know, we, we had 93% fewer trays waiting assembly, 81% reduction in sort of the expedited sterilization process that ideally wouldn't be used, a 66% reduction in flow time. So the amount of time it took from the instruments to be done in the operating room all the way through to being ready to send back that time was reduced from about 10 and a half hours to three and a half hours.

Mark Graban (42m 37s):

It's, it's very similar to the scale of improvement that Mr. O'Neill talked about in this video clips. And we had gone through and calculated, if you will, the theoretical limit, if this process was nothing but value-added times stitched together, it was 3.2 hours. We got it down to 3.6. So, you know, you can look at quantitative satisfaction. We did surveys, staff satisfaction engagement rates were higher because we were engaging them and doing the work. And they're satisfied when they're able to accomplish the goals of the organization. A lot of qualitative comments and you can go and read this on the slides if you want, of the staff saying it's less chaotic, the chief of surgery saying my door isn't a revolving door of complaints anymore.

Mark Graban (43m 23s):

This is benefit for the staff that flows through to the surgeons and and to the patients in so many ways. So when we're engaging people and trying to do ambitious things, we use scientific thinking or a three thinking. You know, here's two examples of A three s from back in the day at oaa that we should be aiming for at least an annual rate of improvement of 30 to 50%. And again, sometimes we see so much more is possible, not 3% improvement or 5% improvement, but something more dramatic. So start the wrap up and I'm gonna hand things over to Ken here. As Mr. O'Neill says, what focusing on safety gets you when it's your anchor, it rebuilds trust with people in the workforce.

Mark Graban (44m 8s):

You're walking the walk, you're bringing energy and action even around the core values and key habits that power operational excellence or whatever you might call it, and accelerates this path to habitual excellence for everything that we do.

Paul O'Neill (44m 24s):

The lessons about how to get close to zero in injury rates among the workforce are exactly, precisely the same things that are required to achieve startling excellence in the delivery of health medical care.

Mark Graban (44m 42s):

So we inspire people through focusing on safety, we get better at improvement and it leads to, as he stated, it helps us with our ambition to be the best in the world at everything that we do. So come,

Ken Segel (44m 57s):

Thanks and I'm just gonna give a few hints here about how to grab this framework at this moment. This covid endurance or covid breakthrough moment, three simple hints and I'll sort of tie it to some t techniques that we use.

Ken Segel (45m 21s):

So the first is that it really is all about the leader and the top leader sort of setting the way forward here in a people focused way. And here's Paul on that.

Paul O'Neill (45m 33s):

With leadership, anything is possible and without it, nothing is possible.

Ken Segel (45m 40s):

So a couple other hints before we get to our framework here. One is that there are two times when this kind of change, the step wide change to do something differently are most possible. The first is when a leader is new, when a top leader is new, when habits haven't been set, right? And patterns haven't been set. So that's one time. But that's, that only comes around periodically in each organization. Although we're gonna, we're getting more turnover as we all know. But the second is when things have fundamentally changed in the environment and, and what I think we as leaders in healthcare are not realizing is our people are expecting us to change in reaction to all that we've been through together.

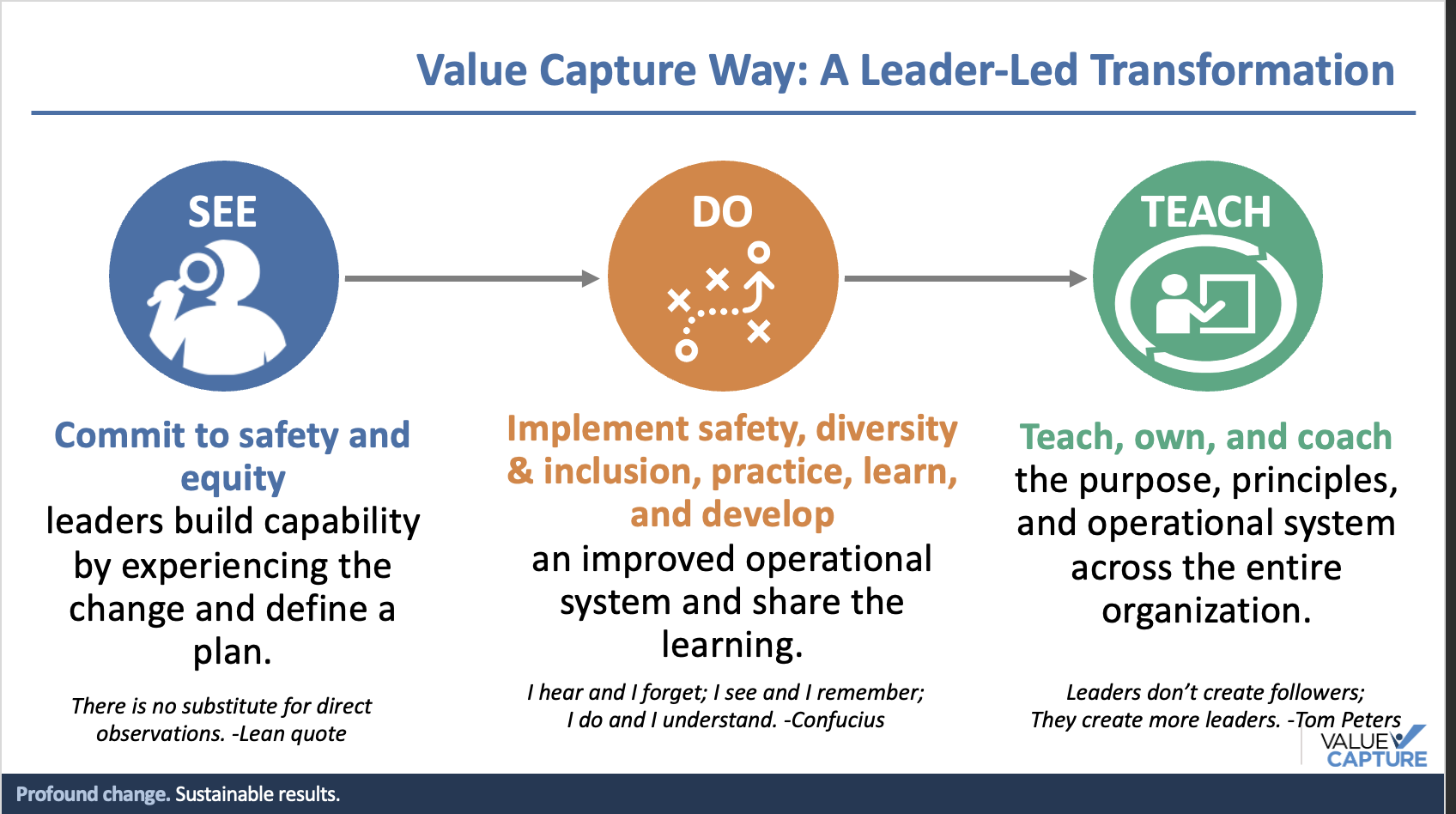

Ken Segel (46m 24s):

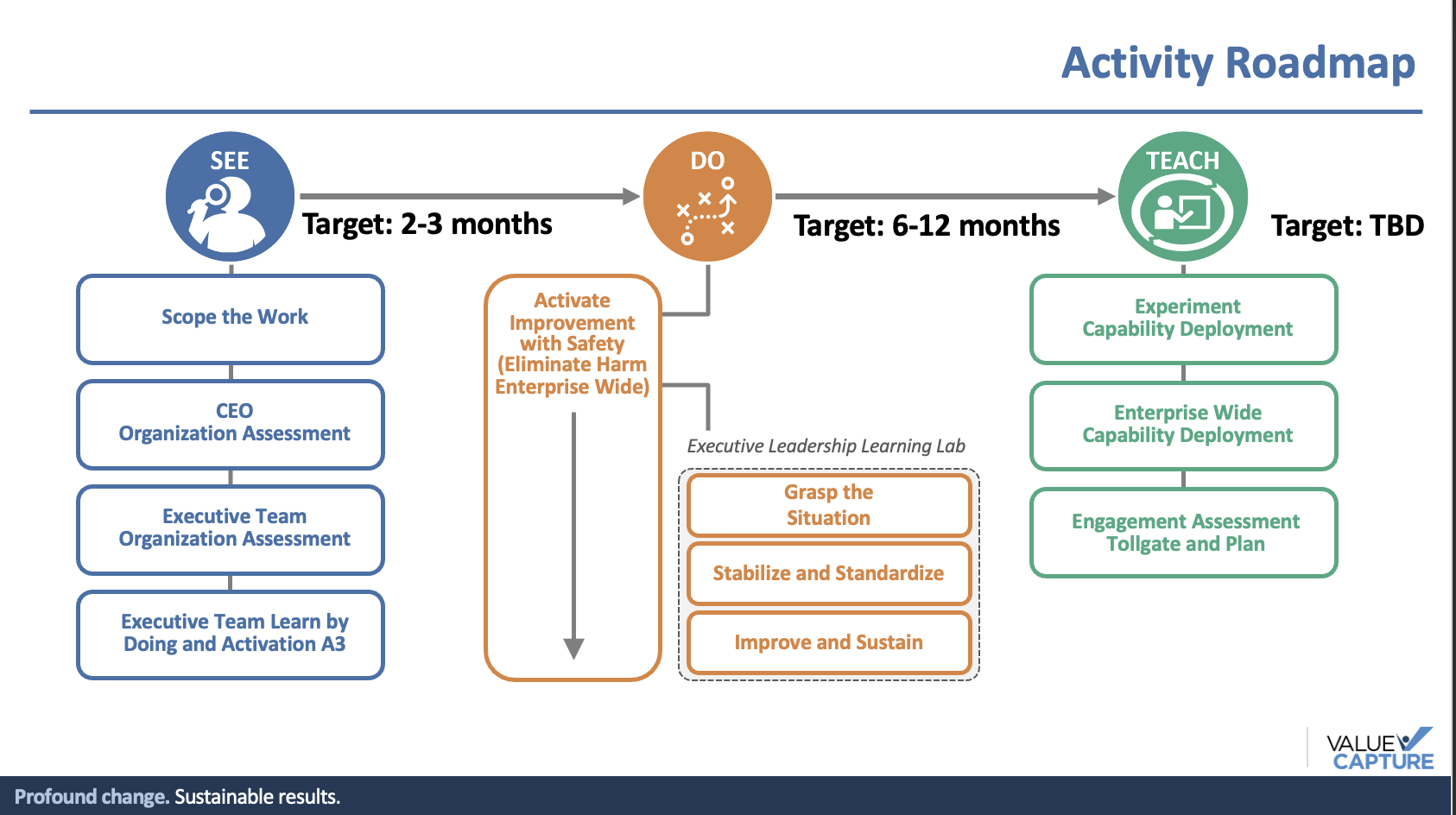

There was a nurse that wrote an op-ed and a national paper saying, I expected more would've changed my organization by now. And so I'm encouraging us to, this is one of those moments when we can make that stepwise change. The third thing is it's awfully hard to change through sort of a meeting based set of new discussions as the way to do it. And so we are passionate about an approach which says first we have to get leaders to see together, to go into the organization to see the current state and then reflect together against these principles and take stock and then set a plan to begin to define a target state that they'd like to move toward. And then do that. So that's what we do with leaders and then we've gotta start, it doesn't matter to just put a plan on paper or believe differently.

Ken Segel (47m 9s):

You have to be actually rolling your sleeves up as a leader close enough to know what it looks like when you're changing these things, but then being pulled back to your level and thinking about what the implications are. And so that's the next thing the do part of this. And then the third part is in healthcare we like to talk about spread sometimes almost in a copy and paste way. Well if this unit figured out that's the best way everybody should do it. But it spreads through capability, it spreads through building people with using these principles to then as they learn it together, to then go and drive it across the organization into the other areas that they lead. So I want us passionately in healthcare to realize spread happens through people development.

Ken Segel (47m 51s):

It doesn't happen through copy and paste. Ok. All right, so an activity roadmap for thinking about this. And Mark and I are happy to talk to anybody who's interested in more details about how to move this direction. But a guided self-assessment with the top leader and then with the rest of the leadership team, as I said, to go see together so you can know together and set a different plan together. And then usually the plan involves a change in safety that's gonna affect everybody across the organization at some level and begin to build the principles that everybody can touch while going simultaneously. If you see this piece executive learning lab deep in one area to solve a key business problem, like the challenge to Paul's controller at Alcoa or the the workforce staffing issues that we have, the performance issues, the need for more revenue which are tied to staffing, solving that in a way that ties all the systems together powerfully and goes forward.

Ken Segel (48m 49s):

And then spreading to the capability. So remembering you gotta change the work system. You can't in healthcare, we fell in love with management system changes the last few years, but you don't get the numbers from management systems. They're built to lock in the gains and keep the culture moving forward. You get the change from moving the work system. So that's what we have to do. And now I'm gonna turn it back to Mark for a final call to action. Yeah,

Mark Graban (49m 17s):

So there's been a lot that we've learned during covid times, you know, of of, of organizations challenging themselves and their people to accomplish new things that we were forced into organizations where leaders performed better when it came to employee health and safety through Covid times because they stuck to principles of not wanting to send people into harms way without having the resources they need. There's a difference between saying, making excuses that the prices have gone up for things versus organizations to say we're gonna spend what it takes to protect our people and we'll figure it out later.

Mark Graban (50m 2s):

Like, which organization is gonna be on a better path toward habitual excellence as the world recovers. I think it's the one that will be supporting that we're supporting their employees and demonstrating it in very public ways and we hope people would be inspired by this poly framework, this playbook and, and the examples of others who have used it. So Ken and I have a shared hypothesis. We hope you would agree and we're gonna have some surveying and polls afterward. We would love to hear your reactions that our hypothesis is that if organizations follow this playbook or a reasonable adaptation of it, these organizations will see dramatically better safety performance.

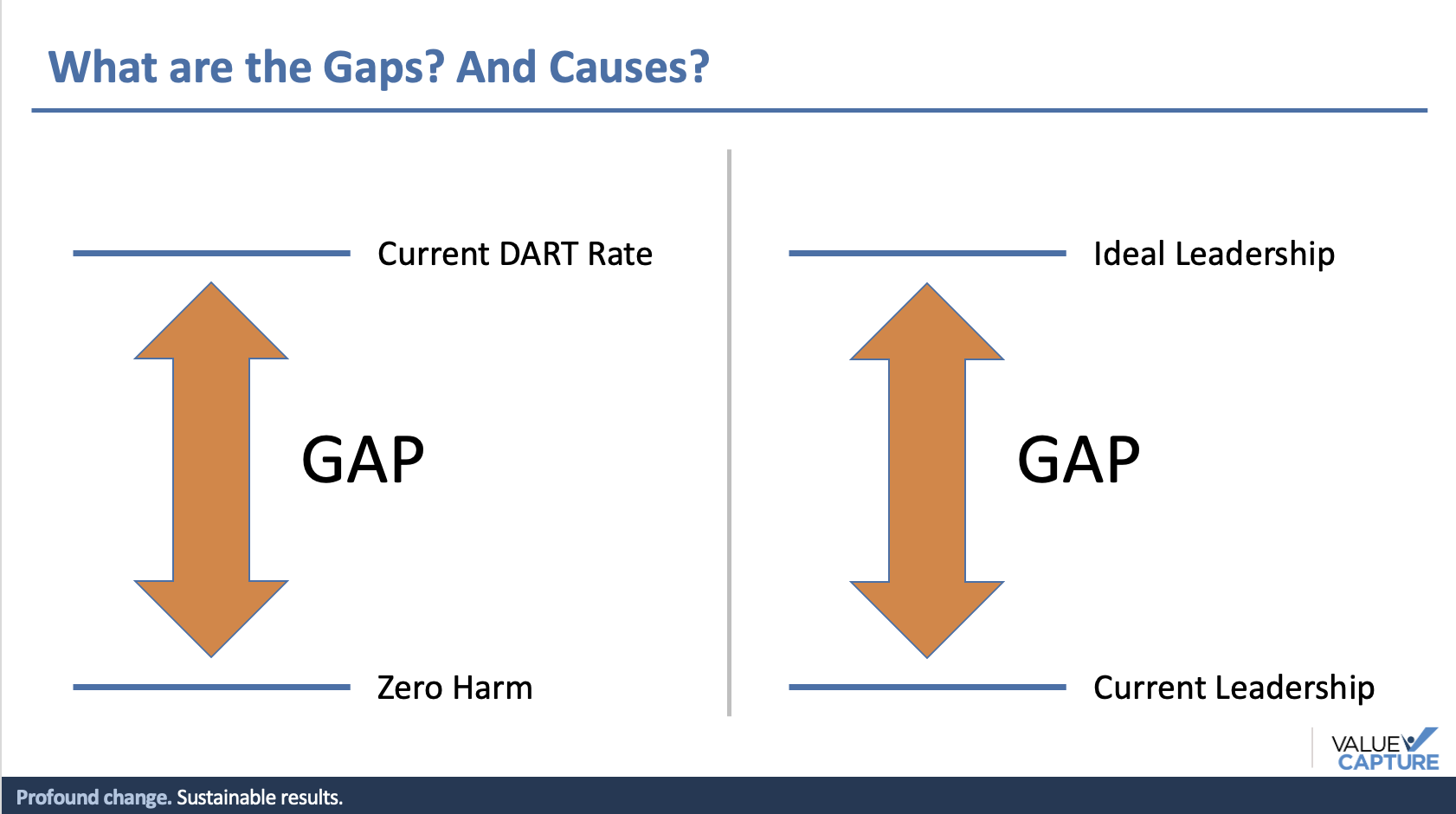

Mark Graban (50m 44s):

They'll have significantly higher employee retention, they'll have more engagement in their habitual excellence journey. How do people get motivated to participate in all sorts of improvement work? They'll perform better in their KPIs in the bottom line. So in the survey we'd love to hear if you agree how much you might agree with this hypothesis. Cause we, a lot of it comes back to identifying gaps. What's our current gap between our dart rate and zero harm? Notice we're not comparing our dart rate to industry average. What is the gap between our dart rate and zero and what are the causes?

Mark Graban (51m 25s):

Why do we have a gap? If part of that is caused by a gap between what we might describe as ideal leadership, meaning the principles, the behaviors, is there a gap in our approach to leadership? And we'll, we'll kind of wrap up with one more thought from Paul Neil.

Paul O'Neill (51m 46s):

You know, again it with taking away the excuses, give it to me. If we, if you tell me there are barriers that need to be rolled away, I will roll over the barriers. There weren't any, you know, it was just an excuse nobody had really examined. How the hell can we do this? We will do it.

Mark Graban (52m 4s):

I love the passion that's on display there, you know, that drive for, and he was talking about something relatively mundane like closing the books faster at the US Treasury. Like imagine how much more people could rally behind the idea of reducing harm to staff into patients. So, you know, we hope today that that, that we've, we've shared some ideas that that may be challenging, but we hope you find that energizing and inspiring. You know, we would love to talk, we'd love to hear your feedback in different ways after the session here. You know, what from the poly playbook gives you the most energy as a leader? If he were here, what questions would you have for him?

Mark Graban (52m 46s):

What questions do you think he would want you to ask? When you think about going deeper with these ideas, what are the biggest barriers that you would have to overcome or the excuses you might have to remove and, you know, to think individually, what are your next steps? Which actions would you take? So before we, we go into Q&A and we, we hit our goal of leaving some time for questions. We'll encourage you to keep submitting those. We have a post-webinar poll, so it's a little bit of the traditional at the end, what'd you like about the webinar, What could have been better? But there are some kinda specific questions related to poly's three questions and these barriers to habitual excellence. If, if you take the survey, we will share the results with everybody.

Mark Graban (53m 29s):

You can use your phone right now, you can scan the QR code, Sara from our team is putting a link in the chat and that link will come in the follow-up email that you get later today. So we'd love to, to hear what some of your thoughts are and, and this information will be here on this next slide, the QR code and the website is there. You can see our email addresses. And again, if you go to value capture llc.com/playbook webinar, you can find video clips and you know the ebook links and a lot of free information that, that we hope you'll find interesting and helpful.

Mark Graban (54m 12s):

So, so Ken is, are any other kind of, you know, call to action or, or thoughts that you would wanna share?

Ken Segel (54m 17s):

No, I'm eager to hear from our colleagues who we've worked with these ideas on and others that are newer to them on what questions do you have and thoughts. And I see we already have one.

Mark Graban (54m 27s):

Yes. So here's a question. Can you share some examples of dashboards that detect, that depict patient or workplace safety in a hospital setting?

Ken Segel (54m 41s):

Yeah. And absolutely we can, there's, you know, both from visual boards on the units themselves to roll up sort of dashboards that are being looked at by some of the pioneers. Absolutely, we can. So either in follow up to everyone or you know, please get in touch with us and we can share some specific examples with you. Absolutely.

Mark Graban (55m 3s):

Yeah. Cause I think there's a couple different levels of it. There's the more traditional, I I guess is, you know, monthly metrics board where you can see goals and improvement and progress. And I, you know, think at it's best, you know, we see where organizations, you know, are using methods like strategy deployment where we're helping them connect activity big initiatives to, to goals and, and to measures. But I think there's, there's still this opportunity when you see the real-time data like that, that's even more powerful, even more helpful. Cause you know, back to this idea of see, solve and share and, and solve problems to root very quickly.

Mark Graban (55m 46s):

You, you don't wanna wait until you see a data point in a monthly report. You're still gonna have the monthly metric, but you need the real-time data, the real-time problem solving to really drive progress faster.

Ken Segel (55m 59s):

Yeah, couldn't agree. And the, the, the dashboard has to feed that sort of real-time action. And one health system we can talk about is, you know, the leadership team came to together every morning and went through the root causes on every death that it occurred, expected or unexpected, and any harm that happened to an employee or a patient. And then, and then of course the electronic sharing of that. So in person electronic sharing back by a dashboard. Thanks, Mark for adding the real-time imperative.

Mark Graban (56m 30s):

So there's another question. I think you know, Paul or Ken, you know, you know, you, you were around him and, and know some of that history. So the question of, you know, Mr. O'Neill was in, you know, industrial company executive and CEO, he was in government. What piqued his interest to try to get involved with mentoring healthcare leaders?

Ken Segel (56m 49s):

Yeah, it was interesting when we first approached him coming out of healthcare and thinking that there, you know, we needed help, he made an interesting comment and that was that he felt that the two sectors in the United States economy that had benefited the least from the ideas of sort of transformative, continuous improvement, but were in a way the most important to all of us are certainly vitally important were education and healthcare. And that he was willing to volunteer and try to share what he knew and, and learn what some of the challenges were and you know, and, and offer this sort of framework of principles-based, you know, aggressive aspirational improvement and try to help it in these crucial sectors that we all depend on.

Ken Segel (57m 40s):

Yeah.

Mark Graban (57m 42s):

So another question, this is something I hear a lot from people, I get pushback in our organization when we bring up the idea of zero harm, people will say, well, that's unrealistic. So we shouldn't, we shouldn't say that. We shouldn't set that expectation. How, how do you push back on the pushback?

Ken Segel (58m 0s):

Well, one story mark, I like to tell again from, from, you know, this is a sort of foundation's webinar and way back in the late 1990s when we were getting organized to push for zero harm for of the first in American healthcare around infections, healthcare-associated infections with our local healthcare community and with the CDC, our friends at the CDC, a doctor a, a well-respected doctor, challenged the group and Paul specifically by saying, you know, we don't even have the science to prevent all healthcare-associated infections of that particular type yet. So it's literally impossible right now.

Ken Segel (58m 43s):

And the room paused and, you know, the the clinical leader had sort of brought the layperson seemingly, you know, to a standstill. But Paul jumped on it and in a very excited way said, you know, to this doctor, that is fabulous because we can be the region that does the research and gets the grants from the NIH that can figure out that lasted crim of science. So we can actually do it. Like that's part of it. We don't know how we're gonna get it done. And another thing, you know, and I'll just bridge to this, Paul would say this a lot when you saw him around Alcoa people, he'd say, I don't know how we're gonna do it, but I have enormous faith in you and I know that we can do it together just using these background principles, but you can do it.

Ken Segel (59m 27s):

We can do it. We're in this together. And it's that as and as I get to my late youth, I talk a lot about that aspirational spirit behind all of this. That all of us belonging, all of us taking this and realizing we can do really great things, really exciting things that matter to us as people if we're willing to sort of go for it and try to use the right basic principles. So that's kind of the spirit that I would see around Paul in these challenging moments and in these just, you know, make it, you know, it was always challenging work, but make it, make it fun. Make it exciting. Yeah.

Mark Graban (1h 0m 3s):

Yeah. Well, thank you Ken. I think, you know, the thing I would add before we wrap up here, I mean, I think talk of zero harm gets discouraging or demoralizing when it's just a slogan. So again, don't do that. But that goal followed up with consistent leadership and progress and, and shifting, you know, the, it's not possible to, we haven't figured out how yet. And you know, I think the other thing people fear is if we set this goal of zero and we want 50% improvement every year, don't punish progress. If, if you set a goal of 50% and somebody does 42% improvement, they shouldn't be afraid of being inspired for not hitting their goal or their target like this.

Mark Graban (1h 0m 51s):

This requires collaboration and support and problem solving and leadership. And I said just doing the work.

Ken Segel (1h 0m 58s):

Absolutely. And it takes a little while to get it going, but you can have breakthroughs fast, which is great. And then it takes a long time for people to really believe things have fundamentally shifted. And that's just the way it's, and that's part of that obligation of leadership. But if we're not running long-term focused institutions in healthcare, who should be? Right?

Mark Graban (1h 1m 22s):

Well, Ken, thank you for final thoughts here. Thank you today, everybody who attended and most everybody stuck with us to the end. So there's one measure of value there. We appreciate everyone staying on here. We, we hope you got a lot out of this. Again, please fill out the post-webinar poll that'll be open for a couple more days. We'd love to hear your feedback. We'd love to talk to you individually. If there's other questions or things that you wanna explore, you can find both of us through email addresses that you see on screen. You can go to our website, value capture llc.com. You can contact us there, you can find us on LinkedIn.

Mark Graban (1h 2m 2s):

And then just final mention again, free resources including eBooks, videos, deeper dives, including The Playbook for Habitual Excellence publication, another book called Lasting Impact, which is quotes and stories from others who learned from Mr. O'Neill and were mentored by him. Those are all available valuecapturellc.com/playbookwebinar. Thank you for the, thanks that, that people are putting in the chat here. Terrific overview. Thanks for the time to do some deep reflection. Just a couple of comments and they're happy to inspire that. So on behalf of the value capture team, you know, thank you everybody for being here.

Mark Graban (1h 2m 46s):

Ken, I'll let you say the final thank you.

Ken Segel (1h 2m 48s):

Yeah, thanks. And I'm, I'm inspired by everyone. And one of the things, you know, we've talked a lot about the Paul O'Neill framework and one of the things about Paul was he would say it, it's in all of us. We all have this in us, formal leaders, informal leaders, and it's not about him. He was just trying to, you know, help people in as many sectors as possible get this done so we'd realize we can do it. So we can do it. You are doing it. You inspire us. Thank you.

Mark Graban (1h 3m 12s):

Well, thank you again for listening to the webinar recording. Again, if you'd like to see the slides, the video version of it to share with others, maybe all sorts of other links and free resources, you can go to valuecapturellc.com/webinars. Look for the orange button, link the top of the page there, and it'll take you to the registration to get all of this again for free.

Thanks for listening to Habitual Excellence presented by Value Capture. We hope you'll subscribe to the podcast and please also rate and review it in your favorite podcast directory or app. To learn more about value capture and how we can help your organization on this journey to habitual excellence, visit our website at www.valuecapturellc.com.

.jpg)

Written by Sara Thompson

Sara is responsible for creating, editing, and curating content that inspires health systems to produce perfect health with zero harm, wait or waste — for patients, team, enterprise, and community. She is responsible for driving the digital marketing for Value Capture and collaborating on the overall marketing strategy to build awareness of Value Capture’s mission and services.

Submit a comment